The Effects of the JCPOA on the Iranian Economy

/Michael Schwartz, AIC Research Associate,

Kriyana Reddy, AIC Research Associate,

Dr. Reza Ghorashi, Professor of Economics at Stockton University & AIC Publications Review Committee Member

Introduction

Over one year has passed since the formal implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed by the US and P5+1 members (China, France, Germany, Russia, and the UK), which lifted certain “nuclear-related secondary sanctions,” on various Iranian business sectors.[1] All parties to the JCPOA agreed to implementing it “in good faith and in a constructive atmosphere” and to “refrain from any policy specifically intended to ... affect the normalization of trade and economic relations with Iran.”[2] While initially the JCPOA was met with optimism, critics in both Tehran and Washington have challenged the effectiveness and potential benefits of the agreement. Iranian public opinion remains steadfastly in support of the deal, but the reality of Iran’s long transition from economic isolation has curbed some enthusiasm. While the JCPOA has created significant opportunities for economic growth and normalization, the Iranian public has not yet seen many tangible economic benefits.

Economic Effects of the JCPOA

In the six-month period following the agreement to implement the JCPOA, Iran gained access to $4.2 billion in assets and increased export earnings by over $7 billion. The country is projected to recover to over $100 billion in formerly frozen monetary assets overseas.[3] In addition to unfrozen assets, gross total relief to Iran as a result of the deal is calculated to be roughly $11 billion, significantly higher than original estimates by the US government.[4]

The benefits that Iran received from the deal are spread out over the multiple sectors impacted by the JCPOA; however, the largest beneficiary of Iran’s relief is the energy sector. In the period following the agreement to implement the JCPOA, oil exports rose by “about 400,000 barrels per day…earning Iran approximately $5 billion in additional revenues over six months.”[5] Despite a global supply glut hurting crude prices production and prices, oil and natural gas revenues were expected to reach $41 billion for the fiscal year ending March, 2017.[6]

Foreign investment is another area where Iran is also expected to see gains. New FDI projects went from three in 2013 to eight in 2014, and nine in 2015, but in the first quarter of 2016, there were 22, with South Korea and Germany contributing the most, at a total of$2.15 billion committed.[7] On January 15th, 2017, the Iranian parliament agreed to a five-year economic development plan, which allows the government to add an annual average of $30 billion in foreign financing, in addition to $15 billion in yearly direct investment, and up to $20 billion in FDI from local partners. This inflow of capital greatly surpasses the average high of $4 billion of annual FDI during the sanctions period.[8] In addition, Iran has bought a 2.8 percent share in China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which promotes Asian FDI projects.[9]

Source: Cara Lyttle, “FDI in Iran soars with sanctions relief”

In 2016, Iran had a GDP of $393.7 billion, which is expected to rise in 2017 by 5.2% according to the World Bank, largely due to increased oil production revenues and FDI projects.[10] While Rouhani’s chief of staff, Mohammad Nahavandian, has claimed “8 percent [GDP growth] is feasible,” Emirates NBD senior economist Jean-Paul Pigat asserted it is unlikely Iran will reach this optimistic mark.[11] While the magnitude of long-term changes in oil prices remains uncertain, overall growth in the Iranian economy is probable over the coming years. The economy shows great potential and momentum—a population of 80 million people, a growing middle class, and a dynamism that makes it the “largest emerging market in the world and the largest economic market outside the G20.” Should sanctions relief remain intact, McKinsey Global Institute estimates that Iran “could increase its GDP by $1 trillion and create nine million jobs by 2035.”[12]

Source: Pigat, “Iran FDI Update”

The effects of the JCPOA on Iran’s economy are diverse, varying across numerous sectors. The following is a breakdown of some of those effects by industry.

Finance and Banking

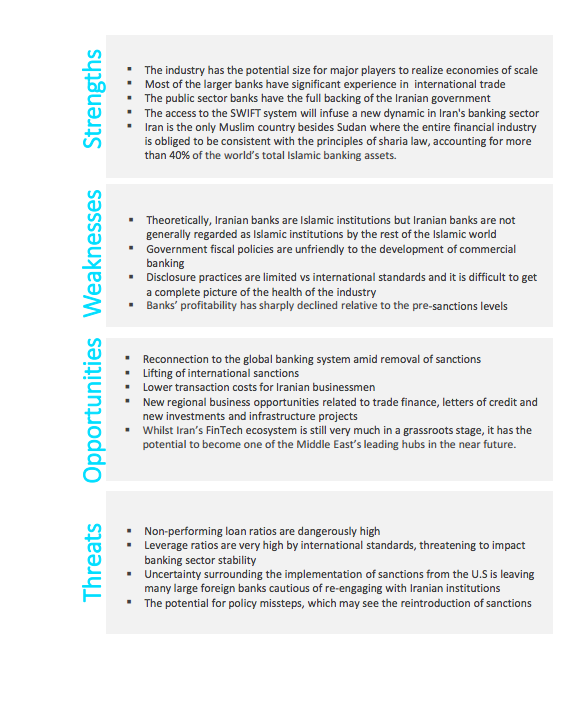

Despite the opportunities from the JCPOA, Iran’s financial system continues to face fundamental economic challenges. Problems include corruption, weak central bank liquidity, non-performing loans, a lack of modern banking practices, and Iranian security monitoring the sector. According to the World Bank, Iran ranks 118th in the organization’s index on the ease of doing business.[13] One senior Tehran banker notes the economic isolation’s negative effects: “Our banking system, like our economy has been isolated and has no idea what has happened in the world over the past decades.” These factors might cause western banks to limit their activity within the country if reforms are not pursued. Mortez Bina, a senior risk manager at the Middle East Bank, warns about the risks of not pursuing reforms: “Foreign investors will not come easily. If we don’t make reforms, we will be in the same situation in five years’ time. …We are behind… if we had observed international standards, our banking crisis would had been less severe.”[14] To face these challenges, Veliollah Seif, Iran’s central bank governor, has proposed Iranian banks need to be reintegrated with foreign banks in the global economy and international standards for financial regulation and compliance must be met.[15]

Many European and American foreign banks are not investing in Iran because they fear fines from the US Justice Department for violating the remaining US sanctions, which prohibit any foreign deals with the IRGC and restrict Iranian use of US dollars. Due to the opaque Iranian economy, companies fear accidental connections to the IRGC and the large fines this would entail. As one senior European official noted, “There is going to be this large grey area that will scare European banks.” Further risks stem from the possibility that the Trump Administration could “tear up” the JCPOA, reinstate the comprehensive sanctions, and take punitive measures against any corporations connected to Iran.[16]

Source: Junemann, “Banking Industry Iran: Current Status, Opportunities, Threats”

Despite the difficulties of reintegrating the Iranian banking industry, some foreign banks willing to risk investment in the country have opened or are in the process of opening new offices in Iran. In June 2016, Iran’s central bank claimed: “Two hundred small and medium-sized international banks have started correspondent relationships with Iranian banks.”[17] For example, Germany’s Europaeisch-Iranische Handelsbank AG (EIH), Italy’s Mediobanca and Banca Popolare di Sondrio, Oman’s Muscat SAOG, India’s UCO Bank Ltd., and South Korea’s Woori Bank already have or are planning to establish operations in Iran. The major European and American financial institutions, however, have kept out of the country, largely due to primary sanctions that remain in effect.[18]

In March 2012, all 30 Iranian banks were disconnected from SWIFT (the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications), which is used globally to transfer capital across international borders. This effectively severed Iran’s ties to the global financial system. Following the implementation of the JCPOA, Iranian banks are now allowed to re-engage with the SWIFT network, although concerns over doing business in Iran continue to limit foreign transactions.

Since JCPOA implementation, Iranian financial authorities have been planning to end the dual-exchange rate system and have taken important steps in that direction. Prior to the lifting of sanctions, there was a large gap between the rates set by the Iranian Central bank and the global market, which peaked in early 2013 when the Iranian central bank set the Rial/USD exchange rate at about 11,000 but the open market placed it at about 38,000. President Rouhani has done much to bridge this gap since taking office late in 2013, and as of December 2016, the official rate was approximately 30,000, while the market rate was about 35,000. This new single exchange rate policy would eliminate the gap completely and allow “commercial lenders to buy foreign currencies using rial rates set by the market rather than those dictated by the central bank.” It would remove another barrier to foreign direct investment, further enabling the rebuilding of the Iranian economy and moving it toward true participation in the global marketplace.[19]

For Iran, improving its banking industry is essential to maximize the potential of the JCPOA and meet its 2025 vision. While ILIA’s report on the Iranian banking industry admits the remaining US sanctions will limit short-term growth, the first milestone to normalization and integration into the world economy has been achieved.[20] More foreign transactions and investments can be expected in the coming years, but progress will be gradual.

Insurance

Overall, sanctions relief is expected to boost the Iranian insurance market in 2017. For insurance companies, Iran is an enticing emerging market. Axco Insurance Information Services reports that Iran is the largest non-life insurance market in the MENA region, as well as the 29th largest globally. Tim Yeates, managing director of Axco, asserts, “Despite all the challenges Iran has faced over the past few decades, Iran offers huge opportunities, which we see only growing as there is more foreign investment; however, it’s important to understand the risks and challenges that the Iranian market offers.”[21] Repealing the 2012 ban, insurers and reinsurers are also now allowed to cover Iranian oil companies, cargo, ships, and port authorities.[22] Although US sanctions continue to restrict parts of Iran’s insurance sector, there is more opportunity for exchange between Iranian firms and foreign partners than previously.[23] For instance, EU insurers and reinsurers remain interested in pursuing business in Iran. As of November 2016, CEO of Lloyds, Inga Beale, met with Abdolnaser Hemmati, president of the Central Insurance of Iran, over potentially expanding into Iran.[24] Likewise, Mehr News reported in March 2017 Victor Peignet, CEO of France’s SCOR Global P&C met with Hemmati to discuss increasing insurance ties. After the meeting, Hemmati stated: “We hope that insurance relations between the two countries will be expanded within framework of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and removal of restrictive conditions rooted in unresolved sanctions against some Iranian companies.”[25] Additionally, in 2016, one US insurer received special authorization to cover Iranian oil cargos.[26] There is still, however, concern regarding investments that could potentially facilitate terrorism. Most US banks are reluctant to make loans for business ventures in Iran due to the penalties outlined in the JCPOA for engagement in activities that might aid terrorism.[27] While US and EU insurers and reinsurers will gradually enter the emerging market, their Asian counterparts will likely march ahead—while still limiting risk—to capture the market. In the future, investors and insurers can expect the opening of Iran’s insurance space to be slow; nevertheless, significant progress has been made since the implementation of the JCPOA.

Energy and Petrochemical

In the Iranian energy sector, the JCPOA was met with expectations of a revival of Iranian petrochemical production and exports, which had been severely constrained by sanctions that limited Iran’s export markets, excluded Iran from the global financial system, prevented new American and EU investments, and forced European International Oil Companies’ (IOC) to leave the country. The JCPOA states the US has formally ceased “efforts to reduce Iran’s crude oil sales, including limitations on the quantities of Iranian crude sold, the jurisdictions that can purchase Iranian crude oil, and how Iranian oil revenues can be used.”[28] Therefore, non-US persons are now allowed to purchase, sell, transport, and acquire Iranian oil if the transactions “do not involve persons on the SDN List.”[29] These transactions, however, must be executed without using the US financial system.

In the year since the implementation of the JCPOA, the Iranian government has increased crude oil production to 3.9 million barrels per day (b/d), an increase of roughly a million b/d from production during the sanctions years.[30] Iranian Energy Minister Bijan Zanganeh stated that Iran was close to its target of 4 million b/d, which the country had produced prior to the 2012 nuclear sanctions. While the November 2016 OPEC deal allowed Iran to return to pre-sanctions output, Iran’s increase is slightly more than its agreed upon production cap (3.8 b/d).[31] By allowing Iran to return to its pre-sanctions output levels, OPEC implicitly confirmed Iran’s claim that its lower production during sanctions was an “unjust” anomaly. This lets Iran continue to produce, while OPEC nations and other parties to the agreement such as Russia are required to cut production.

In conjunction with increased production, Iran’s oil exports are also expected to climb. While Iran has had difficulty finding buyers for its oil in the global supply glut, crude and condensate exports for February 2017 are expected to reach 2.20 million b/d, a modest increase from 2.16 in January. In Asia, Iran’s exports have hit a three-month high of 1.5 million b/d, while in Europe the total remains stagnant at roughly 600,000 b/d. Ralph Leszcynski claims that Europe’s imports of Iranian crude have a history of being higher: “Italy and Spain used to be quite enthusiastic buyers of Iranian crude ... In 2011 they were accounting for respectively 7 and 6 percent of Iranian oil exports.”[32]

The severe international sanctions levied against Iran made its energy industry in dire need of international investment. Zaganeh claims the industry needs the investment of $100 billion or more to reach its production goals. Due to the JCPOA, throughout 2016 a large number of both Eastern and Western IOCs signed memorandums of understanding to develop Iran’s extensive energy reserves. These companies include American-Dutch Schlumberger, British-Dutch Shell, Chinese CNPC, French Total, German Wintershall, Italian Saipem, Japanese Inpex, Norwegian DNO, and Russian Gazprom. While only Total, NIOC, and CNPC have pursued contract finalization, many of the aforementioned IOCs are preparing to do so.[33] Since the implementation of the JCPOA, Shell, however, has remained “cool” to Iranian oil, purchasing only three cargos of crude, a small fraction of what it used to buy, because of the legal challenges and risks of large-scale transactions.[34] Without international investment and the technology it brings, Iran will continue to hold some of the largest oil and natural gas reserves (13% of the global total) but fail to increase its production, which only accounts of 4.7% of the worldwide total.

While increasing crude oil production, Iran will also seek to take more advantage of its massive natural gas reserves, valued at $7 trillion, despite the country’s current low exports. Iran holds one of the largest gas fields in the world, the South Pars, which is currently being developed by Iran’s Petropars and China’s CNPC. In early January 2017, South Pars was producing 500 cu m/d, a substantial increase from the 285 cu m/d in January 2013. Iran expects to add 45 million cu m/d by the end of March.[35] IOCs have recognized the potential for investment in Iran’s growing natural gas industry. Austria’s OMV AG has said that the natural gas market in Iran, is “a big opportunity.” Others remain more bearish: Christopher Haines, head of BMI’s oil and gas division, argues “Iran’s got just a huge amount of potential, but I don’t see anything major happening for some time.”[36] In addition, Total is in negotiations to buy a stake in and help complete Iran’s partly built LNG export facility, essential to exploiting its vast reserves. While this deal faces significant hurdles, gaining an LNG plant would modernize Iran’s natural gas infrastructure.

While sanctions relief has increased Iranian petrochemical production and sales, Iran will need to attract capital and technology to strengthen its oil and natural gas infrastructure in order to meet its long-term goals.

Shipping, Shipbuilding, and Port Sectors

The JCPOA has rescinded the restrictions on Iran’s shipping industry that sought to isolate the country from the global economy. The sanctions against Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Line (IRISL) caused 85% of Iran’s exports and imports to be disrupted and caused insurance companies and international classification societies, which provide technical certificates for ships to travel in international waters, to sever their relationships with IRISL.[37] Rouhani notes the disastrous effects that the sanctions had on shipping: “Formerly, we were under sanctions with respect to shipping areas, leading to a situation in which large vessels did not call at Iranian ports and thus we were inevitably forced to ship the respective goods to our ports by dhows, which imposed enormous expenses on Iran.”[38]

Since the JCPOA, IRISL has sought to revive its previous services and routes. Only twenty days after the implementation of the JCPOA, IRISL revived its Persian Gulf-Europe line. Shortly thereafter, the Azargoun carried thousands of standard shipping containers to Hamburg, marking a resumption of trade after nearly six years.[39] Likewise, the Shipping Corp. of India seeks to revive its shipping lines with Iran to access Central Asian and Middle Eastern markets.[40] In January 2017, Zaganeh announced two Iranian VLCCs were headed to Rotterdam for the first time in five years to export 4 million barrels of crude. In addition, IRISL has sent representatives to ports around the world and attained a $580-million insurance policy on its fleet.

To further restore and expand its shipping industry, Iran has also sought to modernize its fleet. In 2016, Hyundai Heavy Industries Co. signed a $700-million deal with Iran to provide 10 ships for Iran’s state-owned shipping company.[41] The deal constitutes one element of IRISL’s plan to spend nearly $2.5 billion for modernization. Hyundai stated that the deal marks Iran’s first ship order since international sanctions were lifted in early 2016.[42] Likewise, China’s Dalian Shipbuilding Industry Co. is in negotiations with IRISL for the construction and modernization of oil tankers and container ships. The cost of this project is estimated at $8-12 billion and is expected to be completed by 2022.[43]

Iran has increasingly pursued investment in the development of ports on the Indian Ocean to expand its maritime trade routes. In the late 1990s Chinese firms backed the development of the Gwadar Port, in Baluchistan, Pakistan, near the Iranian border. In 2002, in response to China’s development of the Gwadar Port, India began developing Iran’s Chabahar deep-water port, a key Persian Gulf port.[44] Development for this port, however, has been slow, with difficult negotiations and US sanctions causing India to cease development until 2012, and Chinese officials seeking to invest to undermine India. Although China may have been interested in obtaining the contract for construction of this port to increase its presence in the Persian Gulf, after the JCPOA agreement, India and Iransigned an MOU for the project’s completion.[45] India wants to use the Chabahar Port to export its products to Iran and Central Asian countries north of it. While China will unlikely be able to control a large portion of the development of the Chabahar Port, in 2015, CEPC announced its $2.5 billion plan to develop an oil pipeline from Gwadar to Nawabshah Iran, connecting China’s port in the region to Iran.[46]

On the one hand, the Iranian shipping industry will depend on major increases in marketing, construction, and investment to maintain long-term growth. On the other hand, the industry has already seen some success following the JCPOA—the Hyundai Heavy Industries deal, growing shipbuilding interest from China, development of ports, and increased trade with Asia and Africa.[47]

Precious and Non-Precious Metals

Since the implementation of the JCPOA, non-US persons are authorized to buy, sell, and transfer precious and non-precious metals to and from Iran, including silver, gold, base metals, platinum, iridium, osmium, palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, and waste/scrap of precious metal or metal clad with precious metals.[48] With 68 types of metals and minerals amounting to roughly 43 billion metric tons of reserves untapped, sanctions relief will allow Iran to attract investment from foreign companies. The investment space for major global firms is large, but a slump in global metals prices and the challenges of navigating political risk in Iran will slow the entry of mining firms in the Iranian market. Neil Passmore, chief executive of Hannam & Partners, notes the challenges of investment: “Iran absolutely has world-class mining assets, which have hitherto been shrouded from investors, but we're in the depths of one of the darkest, worst downturns in mining for some time.”[49]

Nevertheless, Iran has been trying to lure investors to develop its mining industry. In October, the Indian national aluminium company, NALCO, stated it plans to send an exploration team to Iran to potentially develop a $2 billion smelter, but is also considering projects in Qatar and Oman instead.[50] Likewise, Singapore-based metals trader Trafigura Group Ltd., which re-entered Iranian markets after the implementation of the JCPOA, announced its search for a Persian-speaking executive to oversee business opportunities in the Middle East.[51] While these developments are essential to expanding and restoring the Iranian mining industry, there is still a long way to go before Iran can truly take advantage of its metals and minerals resources. In November 2016, state-owned mining company IMIDRO told an Australian mining conference that Iran’s sector needed $20 billion in investment by 2025.[52]

The short-term results of the JCPOA did not prove promising, with declining metals prices and foreign investors’ wariness about working with the Iranian government thwarting major deals.[53] In the medium term, however, prospects for Iran’s mining sector look brighter. For instance, Iran’s demand for copper is expected to grow by about 3 to 4 percent per year, and Iran has some of the world’s largest undeveloped copper and zinc deposits. [54] Pursuing the development of its commodities industry beyond oil is essential for Iran to diversify its economy. As Robin Bhar, head of metals research at Societe Generale notes, “As [Iran] get more oil revenue, there's no reason why they shouldn't look to diversify the economy and drive metals exports." In the long term, Iran’s resources and low energy costs will help it become a bigger player in the global metals industry.[55]

Automotive Sector

The JCPOA has enabled non-US persons to sell goods and services used in the automotive sector to Iran. Excluded from this element of the JCPOA are US-origin finished vehicles and auto parts, which still cannot be exported to Iran.[56]

Iran’s automotive industry is its second largest (following oil and natural gas) and accounts for nearly 10% of the nation’s GDP and 4% of the labour force. During sanctions, and particularly the last two years before the JCPOA, the industry entered a sharp decline; however, last year proved transformative for Iran’s automotive industry. From March 20 to December 20, roughly 950,000 four-wheeled vehicles were produced in Iran, a 39.1 percent growth in the number of domestically-manufactured vehicles.[57] Additionally, numerous deals between foreign and Iranian firms were successfully arranged. In January 2016, Peugeot-Citroen (PSA Group) signed a €400-million deal with Iran Khodro, a subsidiary of the state-owned Industrial Development and Renovation Organization.[58], [59] Iran Khodro also announced an agreement with Datsun, a subsidiary of Nissan. In addition, Iran’s automotive market has gotten attention from Fiat and Lifan, both of whom are considering the development of new vehicle models for the Iranian market.[60] Because of all of these factors, Iran is set to reach its goal of producing 3 million cars per year by 2025.[61] Until then, carmakers are projected to export some $6 billion in car-related products and $25 billion in car parts.[62]

Nevertheless, investors continue to withhold their money from the automotive industry. Iran must invest nearly €2 billion over the next year to keep the industry alive, but sanctions relief has allowed foreign investments from global automotive giants to cover some of the expected need for investment.[63]

Tourism

Iran’s tourism industry generates approximately $8 billion annually, and is expected to create over 1.9 million Iranian jobs by 2025.[64] After the United States lifted sanctions in 2015, the number of tourists visiting Iran rapidly increased. The country expects, by 2025, to attract a total of nearly 20 million tourists who will spend approximately $30 billion.

The tourism industry appears to be growing, but most foreign public opinion remains stagnant. Polls indicate that a mere 14 percent of Americans hold a favorable view of Iran—the same as prior to the nuclear deal.[65] In contrast, the perception in Iran of tourists is much different. In June 2016, a survey by the Center for International Security Studies at Maryland claims 80.1% of Iranians support American tourism to some degree. [66] Many Iranians have welcoming attitudes that also extend to sharing homes. In the past few years, roughly 36,000 Iranians have offered free lodging to tourists as a means of creating positive experiences for them and exchanging cultural knowledge.[67] The Iranian government is also pushing for an expansion of the tourism industry. Last summer, it authorized the eligibility of citizens of 190 countries to receive 30-day visas.[68]

Source: Mohseni, Gallagher, Ramsay, “Iranian Public Opinion: One Year after the Nuclear Deal”

This government effort will also benefit the hotel and hospitality sector of the tourism industry. With a shortage of hotels, and many in need of renovation, 125 new four- and five-star hotels are currently under construction. Foreign investors have contributed to this construction boom, including Europe's largest hotel group, Accor, and UAE-based Rotana. In addition, German-based InterCity Hotels Group recently reached an agreement with the Iranian government to build 10 new luxury hotels over the next decade.[69]

Public Opinion

In June 2016, a year after the unveiling of the JCPOA, the Centre for International Security Studies at Maryland created a survey of over 1000 Iranians on the perceived effects of the agreement. [70]

Q16 shows a general trend moving from strong enthusiasm for the JCPOA to continuing but less ardent support. In contrast, disapproval of the JCPOA remains relatively static, but with small increases.

The waning enthusiasm for the JCPOA as a whole is reflected in Q5a and Q5b, which indicate a growing sentiment that the economic conditions in Iran have not been improving, and have instead been getting worse or remaining the same. Among participants that claimed Iran’s economy is stagnant or declining, the majority do not blame President Rouhani, but see the causes as outside of his control.

On the topic of living conditions, most Iranians believe they have not improved, but 66% are somewhat optimistic they will in the future.

Regarding foreign investment, most Iranians believed initially after implementation that it would take six months to a year to notice tangible effects. By June 2016, while there was little consensus about the time it will take, most Iranians were less optimistic than they were previously. The general trend and opinion is that whatever positive effects do result, they will probably come later and perhaps be less significant than originally thought.

On unemployment, there is a similar widespread opinion trend that positive change will come later and perhaps be less significant than first expected.

While the majority of Iranians continue to support the JCPOA and believe that there will be some positive results from it, their initial enthusiasm has been tempered by reality. Iranians are learning that while the JCPOA can foster long-term economic growth, the agreement is not a panacea for all of the nation’s economic ills. They see that the agreement is a first step in a large, complex process of addressing Iran’s economic isolation and lack of modern financial policy and physical infrastructure.

Conclusion

Although the JCPOA has shown some promising initial results, the future of it rests in a delicate balance. The “snap back” provision of the JCPOA, which allows the US to re-impose sanctions should Iran engage in any transgressions, adds a tentative element to the agreement.[71] The implications of the snap back are far-reaching; they go well beyond the Iranian economy. If the US suspects Iran of violating the JCPOA, the US may present its allegation to the UN Security Council, after which sanctions would be automatically re-imposed, unless protested by the majority of the members of the UNSC. In this case, a whole new resolution would have to be passed in order for the snap back sanctions to be nullified.[72] Additionally, the US legislature recently passed the Iran Sanctions Extensions Act, giving the US government the authority to re-impose sanctions under the original Iran Sanctions Act of 1996 at any point during the 10-year period between December 31, 2016, and December 31, 2026.[73] It is uncertain whether more sanctions will be lifted by the US government in the foreseeable future.

Despite this uncertainty, the success of major US-based companies in securing business deals in Iran proves that the JCPOA has enabled great changes within the Iranian-American economic relationship. Boeing recently closed a $25-billion deal with Iran Air for civilian aircraft and parts. [74] General Electric applied for OFAC authorization to provide maintenance and sell equipment to Iranian customers.[75] In addition, several smaller firms have utilized General License H to enter into new business agreements with Iran. Despite some lingering cultural and religious wariness, many major global corporations are expanding their field operations, investments, and supply chains in Iranian markets—indicating a growth in investor interest. Nevertheless, the impacts of both US and Iranian politics and instability in the Middle East will be continuing factors influencing foreign investment in Iran.

The JCPOA has had a diverse impact on the Iranian economy, but the economy continues to face ills that could not—and cannot—be solved by sanctions relief alone. For example, unemployment rates in Iran have reached record highs despite the new economic opportunities.[76] Since January 2016, unemployment in Iran has increased from 10.7 to 12.2%.[77] Additionally, many Iranian assets remain frozen by US banks, and while Iranian exports to the US increased, American exports to Iran decreased in 2016, signalling hesitance by many Western companies to expand business activity in Iran. Iran will also face political uncertainty in the coming years—with the upcoming 2017 Iranian elections, President Hassan Rouhani’s economic reforms for an open economy face staunch opposition from Iranian conservatives.

Another major factor impeding the recovery of the Iranian economy is the continuing domination of key industries by Khamenei and his conservative network of supporters. Khamenei-controlled corporations have been receiving the majority of deals: Forbes reported that as of February 2017, private Iranian companies got only 17, while companies with heads appointed by Khamenei got 90. Corporations controlled by Khamenei, including the Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution (IRGC)—a branch of Iran’s Armed Forces—have finalized foreign deals estimated at over $11 billion. Of the 90 deals, the IRGC has large stakes in four through front companies, despite the continuing US sanctions on business connections with the IRGC. Companies that made three of these four deals have yet to be sanctioned, while the fourth still is involved indirectly.[78] Within the key oil and natural gas sector, the IRGC and other forces in the Iranian military-industrial complex continue to hold a strong presence. IRGC members have not only been placed in key positions (e.g., post of oil minister) but also acquired major contracts in offshore energy services.[79] International firms view Iran as a risky investment space, and the inseparability of Iran’s theocratic politics from its national economy will determine the extent to which the JCPOA can create more positive change in the coming years.

The JCPOA has opened business and trade opportunities in numerous Iranian economic sectors, and these changes have already led to significant growth in the Iranian economy. Promoting open economic relations, as well as retaining the sanctions relief programs offered by the JCPOA, will likely lead to greater economic growth--and political stability--in Iran in the coming years. While the JCPOA offers an opportunity for improvements, sustainable economic growth is a long-term process. The JCPOA is a step in the right direction; however, there are no quick fixes; genuine economic growth will be a process of evolution, not revolution.

[1] “JCPOA Implementation,” U.S. Treasury(16 January 2016) p. 2

[2] “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action” (Vienna: 14 July 2015) p.14

[3] Kasra Naji, “Iran Nuclear Deal: Five effects of lifting sanctions,” BBC (18 January 2016)

[4] Steven Mufson, “What ending sanctions on Iran will mean for the country’s economy” (12 August 2015)

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tsvetana Paraskova, “Iran’s Oil, Gas revenues to hit $41B in 2016/2017” Oilprice (16 January 2017)

[7] Cara Lyttle, “FDI in Iran soars with sanctions relief,” Financial Times, (20 June 2016)

[8] Andrew Torchia and Tom Heneghan, “Iran Parliament stresses foreign investment in five-year economic plan,” Reuters (15 January 2017)

[9] Ben Blanchard, “China says Iran joins AIIB as founder member” Reuters (8 April 2015)

[10] “Islamic Republic of Iran” International Monetary Fund, IMF Country Report 17:62 (February 2017) p. 4

[11] Jean-Paul Pigat, “Iran FDI Update” Emirates NBD (8 February 2016)

[12] “Iran without Sanctions: What has changed?” Knowledge at Wharton, (13 December 2016)

[13] Richard Nephew and Elizabeth Rosenberg, “Iran’s broken financial system” Politico, 6 August 2016

[14] Najmeh Bozorgmehr, “Iran’s ‘outdated’ banks hamper efforts to rejoin global economy” Financial Times (19 January 2016)

[15]Ibid

[16] Geoff Dyer, Martin Arnold, Alex Barker, “Sanctions confusion leaves European banks wary of Iran business” Financial Times (17 January 2016)

[17] Thomas Arnold and Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, “Small banks help Iran slowly restore foreign financial ties” Reuters, (15 June 2016)

[18] Golnar Motevalli and Mathew Martin, “Foreign Banks Open in Iran, Central Bank Official Says” Bloomberg (6 November 2016)

[19] Ladane Nasseri, “Iran Puts Trust in Market to Deliver Currency Boost to Recovery” Bloomberg (20 August 2016)

[20] Ibid

[21] Louie Bacani, “Lloyd’s in talks with Iran for expansion” Insurance Business Magazine (21 November 2016)

[22] Jonathan Moss and Jamie Barton, “An update on the lifting of sanctions against Iran” DWF (18 March 2016)

[23] “Iran Insurance Report” BMI Research

[24] Bacani, “Lloyd’s in talks with Iran for expansion”

[25] “Scor eager to boost insurance ties with Iran” Mehr News Agency (5 March 2017)

[26] Moss and Barton, “An update on the lifting of sanctions against Iran”

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Frequently Asked Questions Relating to the Lifting of Certain U.S. Sanctions Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on Implementation Day” U.S Treasury Department, p. 9.

[29] Ibid p. 10.

[30] David Jalilvand, “Iranian Energy: a comeback with hurdles” The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Jauary 2017)

[31] Tasmin Carlisle, “Iran lifts crude oil output to 3.9b/d, supporting rising exports” S&P Platts (27 January 2017)

[32] Osamu Tsukimori and Aaron Sheldrick, “Iran’s oil exports to rise slightly in February” Reuters, (27 January 2017)

[33] Jalilvand, “Iranian Energy: a comeback with hurdles”

[34] Dmitry Zhdannikov, “Despite sanctions relief, Shell still cool on Iranian oil buys” Reuters (10 March 2017)

[35] Carlisle, “Iran lifts crude oil output to 3.9b/d,”

[36] Weixin Zha and Kelly Gilblom, “Money talks louder than Trump for Iran in Natural Gas push” Bloomberg (23 February 2017)

[37] “IRISL to Experience a Boom” IRISL Group (12 March 2017)

[38] “Facilitation of Shipping Activities, Substantial Achievement of JCPOA,” IRISL Group (3 August 2016)

[39] In-Soo Nam, “Hyundai Heavy Gets $700 Million Deal to Build 10 Ships for Iran Shipping Lines” Wall Street Journal (10 December 2016)

[40] Saket Sundria and Debijit Chakraborty, “Top India Shipping Line Reviving Iran Venture to Fight Slump” Bloomberg (2 September 2016)

[41] Nam, “Hyundai Heavy Gets $700 Million Deal”

[42] Ibid.

[43] Chen Aizhu and Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, “China firms push for multi-billion dollar Iran rail and ship deals” Reuters (10 March 2016)

[44] Michael Tanchum, “Iran’s Chabahar Port transforms its position” The Jerusalem Post (January 4, 2014)

[45] Ibid.

[46] Joel Wuthnow, “Posing Problems without an Alliance: China-Iran Relations after the Nuclear Deal”

[47] Ibid.

[48] “Frequently Asked Questions Relating to the Lifting of Certain U.S. Sanctions Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on Implementation Day” U.S Treasury Department, p. 22.

[49] Eric Onstad, “Iran offers mining riches post-sanctions, but investors cautious.”

[50] Ibid

[51] Andy Hoffman, “Trafigura aims to boost metals trading with Post-Sanctions Iran” Bloomberg (6 October 2016)

[52] Onstad, “Iran offers mining riches post-sanctions”

[53] Ibid.

[54] Hoffman, “Trafigura aims to boost metals trading”

[55] Onstad, “Iran offers mining riches post-sanctions”

[56] “Frequently Asked Questions Relating to the Lifting of Certain U.S. Sanctions Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on Implementation Day” U.S Treasury Department, p. 24.

[57] “Iran’s Auto Production Jumps by about 40% in 9 Months” Tasmin News Agency (16 December 2016)

[58] “Iran Auto Sector 2016: Playing for High Stakes” Financial Tribune (1 January 2017)

[59] Kenith Ashtarian, “Iran’s Automatic Industry: A potential draw for investors” UNESCO Report (27 January 2016)

[60] Ibid.

[61] “Nuke deal appears to help Iran’s car making industry” Azer News (23 December 2016)

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

[64] “Iran Tourism: After the Nuclear Deal” SURF Iran (14 July 2016)

[65] Andrew Dugan, “After Nuclear Deal, US Views of Iran Remain Dismal” Gallup (17 February 2016)

[66] Ebrahim Mohseni, Nancy Gallagher, Clay Ramsay, “Iranian Public Opinion One Year after the Nuclear Deal: A Public Opinion Study” The Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (July 2016)

[67] Thomas Erdbrik, “Long Avoided by Tourists, Iran is Suddenly a Hot Destination” The New York Times (8 November 2016)

[68] Behdad Mahichi, “Tourism on the rebound in Iran” Al Jazeera (29 July2016)

[69] Erdbrik, “Long Avoided by Tourists, Iran is Suddenly a Hot Destination”

[70] Mohseni, Gallagher, Ramsay, “Iranian Public Opinion One Year after the Nuclear Deal”

[72] Michele Kelemen, “A Look at How Sanctions Would ‘Snap Back” If iran Violates Nuke Deal” NPR (20 July 2015)

[73] Baker McKenzie, “US - Iran Sanctions Act extended for ten years; OFAC updates Iran FAQs and issues General License J-1” Lexicology (20 December 2016)

[74] Zachary Brez, “6 Months Since Iran Sanctions Relief Lessons and Forecast” Law360 (28 July 2016)

[75] Ibid.

[76] Majid Rafizazdeh, “New empowered, Iran will take a bolder approach in the region” The National(31 December 2016)

[77] “Iran Unemployment Rate” Trading Economics

[78] Heshmat Alavi, “Iran Irony: IRGC and State Firms are Benefiting from JCPOA” Forbes (16 February 16, 2017)

[79] “In Iran, Economic Reforms Hit a Hard Line” Stratfor (13 April 2016)