Return of the Cypress: Iran’s Foreign Policy Ambitions in Central Asia

/By AIC Research Associate Tristan Gutbezahl

Map of Central Asia

Western perceptions of Iran possessing an exclusively Middle Eastern foreign policy obscure the country’s growing interests in Central Asia. The region’s potential as an outlet for political and economic maneuverability in the face of sustained Western sanctions has placed Central Asia at the forefront of Tehran's geopolitical ambitions: President Raisi designated improving relations with Central Asia as “one of the first priorities of the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran" in 2022. Despite Raisi’s ambition, Iran’s moribund economy and international isolation limits its ability to woo partners in Central Asia. This article will explore Iran’s historical connections, current policies, and future vision for a region its ancestors once considered indispensable.

An Ancient History

Iranian culture boasts an ancient legacy in Central Asia, with Persian-speaking peoples such as the Saka (or Scythians) having inhabited the region as early as the seventh-century BC, according to Assyrian sources. The Saka dominated the Eurasian steppes for generations, trading with Greek colonists in modern-day Ukraine and jostling for power against the mighty Achaemenid Empire of Persia. In the following centuries, the modern-day Iranian provinces of Sistan-Baluchestan and Khorasan hosted critical routes for Silk Road merchants to reach the Indian Ocean. Economic connectivity beginning in the early Middle Ages resulted in deep-seated cultural influence. Some of the most revered Persian-speaking poets and scientists of the period hail from Central Asia, most notably Rudaki, who many consider to be the father of Persian poetry. To this day, all five of the Central Asian republics celebrate the Persian new year (Nowruz), to varying extents. Cultural connections notwithstanding, the region posed a significant security threat to Iran during this period; Turkic and Mongol nomads traditionally invaded Iran via its vulnerable northern borders with Central Asia. The subsequent Central Asian conquests of Iran spawned a unique Turko-Persian culture that would dominate the region until the eighteenth-century. The great king Nader Shah’s (“The Sword of Persia”) conquest of the Bukhara Khanate and Khwarazmian Dynasty in 1741 would make him the last Iranian ruler of Turkic origin to control territory in the region.

Iranian political and cultural influence in Central Asia oscillated in the modern period. The tumult of colonialism disrupted the country’s connection with its northern neighbors in the late nineteenth-century; Iranian refugees fleeing the chaos of the Qajar Dynasty constituted 29% of Central Asia’s non-native population in 1890. Later, Soviet control of Central Asia froze Iran’s political relationship with the region for most of the twentieth-century. Iranian interest would only renew after the end of the Cold War in 1991: Iran was among the first countries to recognize the Central Asian republics’ (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) newfound independence. To kickstart relations, Iranian administrators encouraged provincial governments to foster commercial ties with post-Soviet states in the 1990s. Likewise, all five Central Asian republics participated in the 1992 Economic Cooperation Organization summit hosted in Tehran. Though eager to rebuild its political and economic connections with Central Asia, Iranian policymakers feared the independent republics would inspire ethnic nationalism among Turkic minority groups in Iran, particularly Turkmen. Subsequent commitments of non-interference from Central Asian governments and the brutal suppression of ethnic nationalists at home laid separatist anxieties in Iran to rest. Since then, Iran has emphasized its shared cultural history with Central Asia to make inroads in what it views as a critical region for investment, security cooperation, and political influence.

Rebuilding the Silk Road

Trade

Chabahar Port in Sistan-Baluchistan Province

As part of its “Look East” policy, Iran is cultivating new economic partners in Asia to circumvent reliance on Western financial and economic systems. Though Russia and China stand as the pillars of this policy, Iran remains committed to strengthening ties with the growing economies of Central Asia. The economic diplomacy of “Look East” has produced substantial results in the region: trade between Iran and Tajikistan doubled to $121 million between 2020 and 2021. Likewise, Iran and Uzbekistan agreed to double trade to $1 billion in March 2023. That summer, Iran and Uzbekistan signed 15 agreements to enhance preferential trade, technology exchange, counterterrorism cooperation, and other areas of collaboration; the two countries ratified 17 similar agreements the year before. In June 2023, Iranian and Kazakh officials drafted a roadmap to increase bilateral trade to $3 billion, while Iranian investors committed to developing pharmaceutical manufacturing and agriculture in Kazakhstan. Kyrgyzstan hosted an exhibition of Iranian knowledge-based firms in 2022 and has since worked to establish a bilateral free-trade agreement with Iran.

Despite measurable gains in recent years, Iran’s trade with Central Asia remains modest: none of the republics crack Tehran’s top five trading partners. However, this may change as Iran further integrates into the region’s premier multilateral fora. Iran signed a free trade agreement with the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) last December, replacing a temporary arrangement negotiated in 2019. The new deal eliminates tariffs on nearly 90% of all goods exchanged between Iran and the EEU, of whom Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan are members. Likewise, Tehran’s recent accession into the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), China’s chief multilateral working group in Eurasia, is projected to boost trade with Central Asia. Though these developments are certainly positive for Iran, its sanction-riddled economy will continue to limit its ability to trade with the region, regardless of participation in multilateral groups.

In tandem with merchandise and raw materials trade, energy security is essential to Iran’s economic strategy in Central Asia. Despite boasting the second largest natural gas reserves in the world, Iran continues to import natural gas from neighboring Turkmenistan. This is largely a result of US sanctions, which inhibit Iran from procuring the advanced equipment and capital needed to access the full potential of its reserves. Though imports have ebbed since the construction of the South Pars gas facility in 2014, Iran’s growing domestic natural gas consumption is taxing its already strained energy infrastructure: Iran ranked as the world’s fourth largest consumer of natural gas in 2021. Its need for additional natural gas in the face of rising demand and dated infrastructure has only elevated Turkmenistan as a crucial energy partner. Indeed, trade with Turkmenistan in the first half of 2022 exceeded all bilateral trade recorded in 2021 as a result of increased natural gas exports to Iran. This trend is only expected to continue: the latest energy agreement signed in May 2023 directs Turkmenistan to transport 10 million cubic meters of gas a day to Iran.

Infrastructure

Like others seeking opportunity on the steppe, Iran recognizes massive upgrades to regional infrastructure are needed to unlock Central Asia’s vast economic potential. The current Soviet-era transportation and energy networks are notorious for their inefficiency and outright danger, stymieing Central Asia’s global connectivity and regional integration. In response, outside countries have invested immensely in upgrading the region’s ailing infrastructure. Though China remains by far the largest infrastructure investor in Central Asia as part of its “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), Iran has quietly developed its own projects with regional partners. Cooperation with Kazakhstan has been particularly prolific: in 2022, Iran opened a new railroad linking Kazakhstan to Turkey, while the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran railway has been in operation since 2014. In 2019, Iran and Tajikistan jointly pledged to renovate the Istiqlol Tunnel, the so-called “tunnel of death.” In addition to transportation, Iran has committed to developing the region’s energy infrastructure, particularly in Tajikistan. Iran invested heavily in constructing the Sangtuda-2 hydropower plant and is currently supporting Iranian contractors working on the Rogun Dam, which will likely qualify as the tallest dam in the world upon completion.

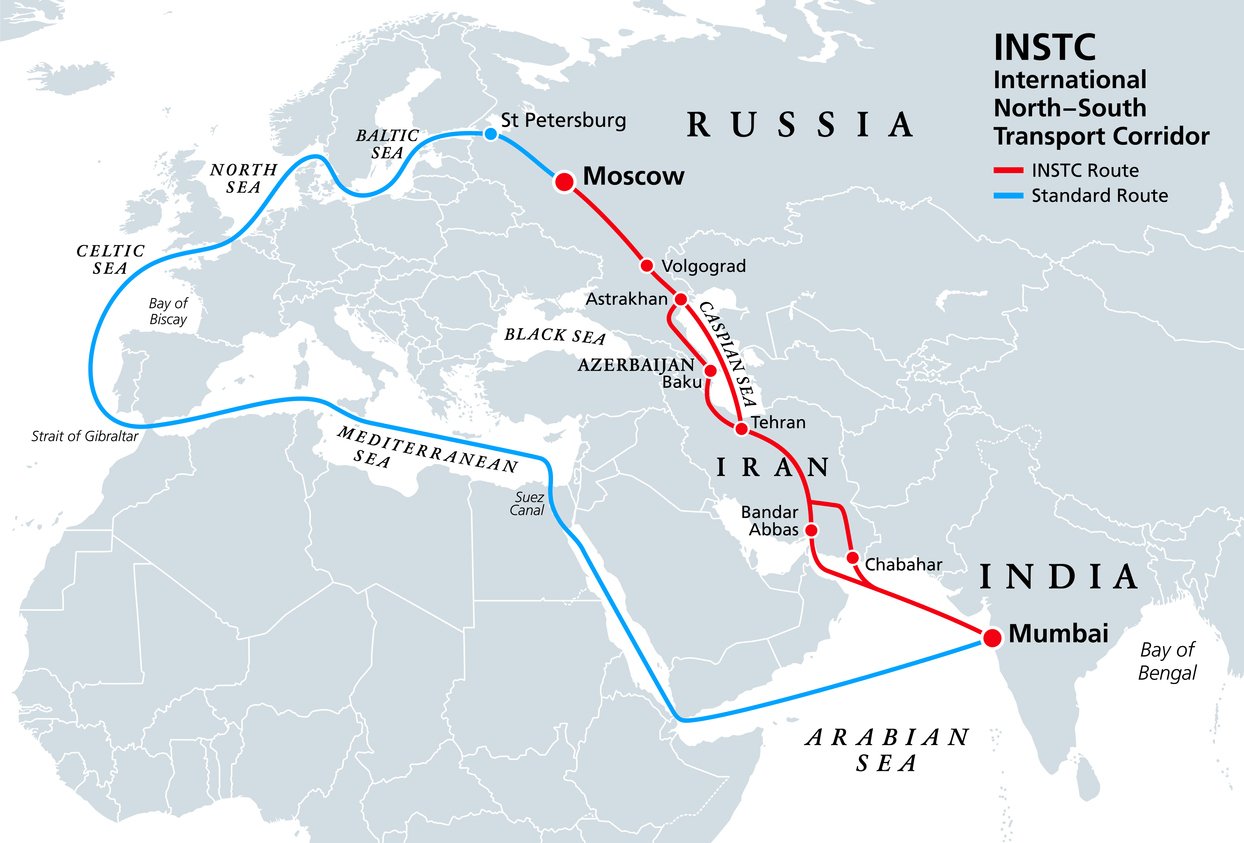

More broadly, Tehran seeks to position itself as a key node to Eurasian trade via the International North South Transit Corridor (INSTC), a transnational infrastructure project designed to connect Russia and the Central Asian republics to the Persian Gulf. Three primary trade arteries centered on the Caspian Sea undergird the INSTC, which will allow Iran to trade with its northern neighbors via land and water. Turkmenistan’s formal accession to the project in July 2023 solidified the third artery running along the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea, offering added insurance to Iran should relations with its rival Azerbaijan, a key country to the INSTC’s western trade artery, sour beyond repair.

Iran’s Chabahar port, with its deep-water capacity and entry to the Indian Ocean, acts as the “Golden Gate” for the INSTC. Access to Chabahar is game-changing for the Central Asian republics, whose landlocked geography inhibits their economies from penetrating global markets. Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have inked bilateral agreements granting access to the port, while Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are pursuing deals of their own with Iran. India is also interested in the port’s potential, having long sought to trade with Central Asia and Russia without traversing adversaries China and Pakistan. India built a $136 million road linking the port to Afghanistan in 2009 and invested $500 million toward the port’s construction in 2017. Indeed, Chabahar’s economic benefits for India and Afghanistan, coupled with its potential as an alternative to China’s BRI system, informed the Trump administration’s decision to lift sanctions on the port in 2018. Foreign investment in Chabahar has coincided with increased economic activity: the port processed 1.5 million tons of goods in the first quarter of 2022, a 33.8% increase from the year prior. Though development of the port is ongoing, it has only grown in importance as Russia's invasion of Ukraine continues to disrupt the vulnerable economies of Central Asia.

Iran's Role in the INSTC

Regional Security After the US

Stability in the region, particularly regarding Afghanistan, remains a central concern to Iran. Though tentatively aligned during the US occupation of Afghanistan, the Taliban’s return to power in 2021 has renewed Iran’s tensions with the extremist group, whose literalist Sunni beliefs and Pashtun chauvinism remain decisively at odds with Iranian Twelver Shi’ism. Even before the US withdrawal, Iran long viewed Afghanistan as a haven for Sunni extremism and has since accused the Taliban of harboring ISIS-K fighters. Likewise, the Taliban resent Iranian support for embattled Shia minorities in Afghanistan, most notably the Persian-speaking Hazara, whom the extremist group has historically oppressed. Cross border issues, namely narcotics and refugees moving westward from Afghanistan to Iran, only exacerbate grievances. Iran regularly admonishes its neighbor for failing to contain these transnational outflows, which its already strained social systems have little capacity to absorb.

Still, jurisdiction over the Helmand River lies at the heart of Iran-Afghanistan antipathy, its disputed water being vital to agriculture and ecosystems on both sides of the border. Though clashes have been recent, the conflict began in 1870 when British officers demarcated the modern Afghan-Iran border along the main artery of the river. After decades of dispute in the first half of the twentieth-century, Iran and Afghanistan signed the Helmand River Treaty of 1973 as a compromise over water rights. However, the treaty was never ratified, leaving a contested status that persists to this day. The Taliban’s decision to redirect the river away from the Hamoun Wetland, a critical source of Iranian drinking water, upended what had previously been an imperfect, yet workable status quo. The results of this policy have been dire: in 2022, Iran claimed that it only received 4% of the water promised by the 1973 treaty. Intense suspicion has since devolved into armed hostility: the two sides engaged in multiple border clashes last year, with deadly consequences. Though cooperation between Iran and Afghanistan remains possible, tensions concerning the Helmand River will likely escalate as climate change lowers water levels across the region.

Like Iran, Tajikistan harbors mutual, if not greater anxiety regarding the security situation in Afghanistan. Dushanbe remains wary of Islamic terrorism seeping across its southern border since the Taliban returned to power in 2021. Conversely, the Taliban fears secular nationalism emanating from Tajikistan will inspire ethnic Tajiks, who comprise a significant percentage of Afghanistan’s diverse population, to revolt against the largely Pashtun extremist group. Historically, Tajikistan served as a cross-border base for anti-Taliban resistance, led by the legendary Afghan-Tajik commander Ahmad Shah Massoud (“The Lion of Panjshir”), prior to the American invasion in 2001. To guard against repeated ethnic rebellion, the Taliban have sought to integrate Afghan Tajiks into their otherwise Pashtun-dominated ranks. The Tehrik-e Taliban Tajikistan (TTT) for example, is an ethnic Tajik militia the Taliban charges with patrolling Afghanistan’s northern border with Tajikistan. Allowing the TTT access to these border provinces is highly provocative, given the militia is descended from the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jamaat Ansarullah (JA) terrorist organization, which waged a multi-year insurgency in Tajikistan.

Balancing against a revived Taliban has brought Iran closer to Tajikistan, the only Central Asian country with a Persian speaking majority. Despite deep cultural connections, ties between the two countries remained frosty until very recently. After the Tajikistan Civil War (1992-1997), the victorious Tajik communists, led by current President Rahmon, accused Iran of assisting elements of the Islamist opposition, namely the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan, leading to decades of embittered relations. Though both countries had agreed to increase security cooperation in 2021, the Iran-Tajikistan “cold war” only came to an official end following President Rahmon’s state visit to Tehran the year after.

Since their diplomatic rapprochement, Iran and Tajikistan have raced to solidify their defense relationship. In June 2022, the two countries held a Joint Security Task Force in Dushanbe to coordinate counterterrorism and anti-narcotic trafficking efforts, which are viewed as directly countering the Taliban. In addition to military-to-military cooperation, Tajikistan is increasingly playing host to Iran’s defense industry. That May, Iran opened a drone factory in Tajikistan capable of producing the Abadil-2 combat model, one of the many Iranian-made drones Russia is currently deploying in Ukraine. The factory serves to mend Iranian-Tajik relations, boost bilateral trade, and help Iranian arms avoid Western sanctions, easing their transport to Russia. Iran’s security relationship with Tajikistan constitutes a coup for its “Look East” policy, which directs policymakers to recruit strategic partners in Asia.

While countering the Taliban remains central to their relationship, Iran maintains interest in the ongoing border disputes between Tajikistan and its Turkic neighbor, Kyrgyzstan. The two have engaged in regular clashes over the contested Ferghana Valley since they achieved independence in 1991. Though Tajikistan remains Iran’s favored security partner in Central Asia, Tehran takes a nuanced approach to Dushanbe’s rivalry with Kyrgyzstan. Iran has explicitly forbid their Tajik partners from deploying Iranian drones against Kyrgyzstan, likely to maintain Tehran’s role as a "neutral arbiter" of Central Asian security. In sum, Iran’s burgeoning security relationship with Tajikistan presents a delicate balancing act. Policymakers in Tehran want Tajikistan strong enough to counter a belligerent Taliban without completely overpowering Kyrgyzstan in the Ferghana Valley, which could upend the balance of power in Central Asia and diminish the influence Tehran wields over Dushanbe.

A New Great Game?

As the region once again finds itself as an arena for great power competition, today’s iteration being a contest between Russia, China, and increasingly the US, middle powers such as Iran will likely employ creative strategies to maintain relevance. Traditionally, Russia exercised hegemony in Central Asia, which is often considered to be part of its geopolitical “backyard.” After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia slowly rebuilt its security influence in the region, culminating with the creation of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) in 2002. However, Russia's decision to invade Ukraine in 2022 radically changed its power-projection capabilities in the region. Moscow’s immense expenditure of capital and manpower in Ukraine, in addition to its subpar military performance, has shattered its army's abilities and reputation, incentivizing Central Asians to seek alternative security arrangements. Likewise, not one of the Central Asian republics has endorsed Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine or recognized Russia’s annexation of eastern Ukrainian provinces, choosing to abstain or not vote at all on UNGA resolutions condemning the invasion. Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan have even sent humanitarian aid to Ukraine in what many perceive as a direct rebuke to Russia. This is not to say Russia no longer plays a vital military and economic role in Central Asia. However, Russia’s relative decline has shaken the security system that has defined the region since the nineteenth-century, opening the door for regional actors to exercise increased autonomy and inviting other great powers to fill the vacuum.

Moscow’s reduced ability to manage security in Central Asia has incentivized China to increase its regional military footprint, often at Russia’s expense. Following the 2008 Financial Crisis, China observed a complementary “Sheriff and Banker” arrangement with Russia, which combined Moscow’s military connections with Beijing’s immense economic capital to promote stability and prosperity in Central Asia. Today, Russia’s preoccupation with Ukraine forces China to take increased responsibility in protecting its investments in the region, most notably BRI infrastructure projects and natural gas pipelines critical to China’s domestic economy. Though China has invested in Central Asian security in the past, most notably its construction of military bases in Tajikistan to deter the Taliban, Russia’s declining regional influence has elevated Chinese involvement to an entirely new level. Now, China continues to loosen Russia’s monopoly as the region’s arms dealer, having supplied 13% of Central Asia’s weapons over the past 5 years. China is also increasingly deploying its own private military companies (PMCs) to protect its investments in Central Asia, challenging Russia’s previously-unchecked security dominance. Most notably however, is China’s commitment to assist law enforcement and internal security agencies in Central Asia with suppressing domestic uprisings, a role Russia previously played. Beijing’s increasing security footprint, coupled with its outsized economic clout in the region, presents an unprecedented challenge to Russia’s long-held domination of Central Asia.

As a tentative ally to China and Russia, Iran is poised to play an intriguing, if not delicate role in the changing geopolitical landscape of Central Asia. Like the Central Asian countries themselves, Iran likely seeks to balance the two great powers, using existing Russian security infrastructure and China’s vast capital reserves to advance Iranian interests in the region. On paper, Iran's support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has brought it closer to Moscow than Beijing. However, this should not discount Iran’s growing economic relationship with China, which is expected to deepen as Beijing’s relations with the US continue to deteriorate. Given its positive relations with both powers, Iran could promote shared interests, such as the INSTC, to foster regional collaboration and defuse counterproductive rivalry. Likewise, the SCO now provides a multilateral forum for Iran to act as a mediator between Russia and China should competition reach a boiling point. In short, Tehran could position itself as a useful buffer between Beijing and Moscow, reaping the benefits of both sides while averting a destructive great power clash that would spell disaster for itself and the region.

This being said, China and Russia remain closely aligned on other international issues, most notably their shared contempt for US global hegemony. Though the two now compete in Central Asia, it has yet to visibly affect bilateral relations. Indeed, it is possible Russia and China will increase regional collaboration as the US dips its toes in the geopolitical competition for Central Asia.

Though Tehran stands on the sidelines of the Russia-China fray, smaller powers directly compete with Iran for influence in Central Asia. Turkey’s quest to expand its cultural and economic sway in the region has led to locking horns with Iran, with whom it already shares significant rivalries in the the south Caucasus and Middle East. Ankara’s recent supply of Bayraktar TB2 combat drones to Kyrgyzstan, likely to counter Tajikistan in the Ferghana Valley, positions Turkey as a regional defense competitor to Iran. Though increasing Turkish activity certainly complicates Iran’s Central Asia policy, growing economic ties likely precludes competition with Ankara from devolving into zero-sum territory.

Lastly, members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), particularly Saudi Arabia, view influence in Central Asia as a means to contain their longstanding-rival Iran. Their cultural forays into the region have posed a particularly vexing challenge to Iran’s vision for Central Asia. Saudi Arabia’s construction of 66 schools in Tajikistan (6 being religious) in 2017 delivered a visible blow to Iran’s soft power in the region. Though GCC influence has yet to reach intolerable levels for Iran, officials in Tehran will continue to monitor the regional activities of their Persian Gulf rivals.

Conclusion

While Iran boasts tangible victories in Central Asia, structural disadvantages will continue to blur its vision for the region. The persistence of Western sanctions places Iran leagues behind its competitors in foreign direct investment, let alone offering alternative economic models to the region. Likewise, the avowedly secular Central Asian governments remain wary of Iran’s theocratic model of governance, preventing Iran from cultivating closer relations with regional actors, as enjoyed by Turkey. Even Iran’s primary partner in the region, Tajikistan, flirts with some of its sworn enemies. The Israel-Hamas War, which Iran is inextricably involved in, will divert Tehran’s attention away from Central Asia, for the time being.

Despite these challenges, Central Asia’s potential as a diplomatic and economic outlet remains too great a lure for Iranian policymakers to abandon. If anything, the increasingly chaotic international system will likely open new opportunities for Iran to exploit in Central Asia, especially in the event of a great power war outside the region. While Iran is unlikely to achieve the commanding heights of power in Central Asia anytime soon, its policies will continue to influence regional politics and measure the level of ambition in Iranian grand strategy.