MYTH vs. FACT: Iranian Architecture

/By Research Associate Clara Keuss

MYTH: Aside from classical and medieval wonders, architecture in Iran is largely limited to dated mid-20th century style structures.

FACT: Iran is not limited to one or two set tyles of architectural design. Iran’s diverse climate and varied cultural eras have inspired talented Iranian architects over the millennia to produce a broad array of impressive and creative structures.

Traditional Iranian Architecture: Diversity in Climate

Iran’s urban centers boast an impressively diverse array of architectural styles. In addition to cultural and political factors, this variety is the product of the country’s climate, which itself varies considerably between regions.

The Yazd Region

The Yazd region, located 270km (~168 miles) southeast of Esfahan and between Iran’s two largest deserts (Dasht-e-Kavir and Dasht-e-Lut), has a dry mid-desert climate. Yazd, the region’s principal city, utilizes a “windcatcher” feature into much of its architecture as a means of combating extreme heat during the days and extreme cold at night. For this reason, Yazd is also called “The City of Windcatchers.” A windcatcher, or Bagdir, allows hot, stagnant air to rise, much like a chimney, and escape homes to naturally cool them– when wind is present, the windcatchers trap the breeze for the building. Another critical reason that windcatchers are used in Iranian architecture is for the economic benefits. Windcatchers, when contrasted with high-level air conditioning systems, are both less expensive and more effective. For this reason, this ancient technology is still used in Iran today. Although the windcatchers’ intricacy and material requirements mean that new units are rarely produced today, there are many existing Bagdir from thousands of years ago which function just as well as they did when first constructed. Today, windcatchers are plentiful in regions such as Yazd, and can be found incorporated into many of the buildings. In some desert regions, windcatchers are also complemented by the “Hozkhaneh”, which utilize wind and water to regulate temperatures inside structures.

Mazandaran and the North

In stark contrast to Yazd, Iran’s northern region, bordering the Caspian Sea and Alborz mountains, features dense forests, snowy mountains, and coastal areas. As the region experiences substantial rainfall, especially in the northernmost areas such as the plains of Mazandaran and neighboring Gilan province, houses are equipped with sloped roofs to divert excess rainwater. Like the windcatchers in Yazd, these sloped roofs exemplify the ingenious ways in which traditional Iranian architects developed innovative means of sustainably interacting with the environment.

Yazd Windcatchers

Mazandaran Houses

In regions such as Azerbaijan in the west and Khorasan in the east, the climate is snowy and cold. There, structures known as “Yakhchal” are used to store ice and preserve it for the summer.

These examples represent but a fraction of the ways in which Iranian architecture has for thousands of years, been shaped by the challenges and necessities of life amidst the county’s diverse climate and environment.

Traditional Iranian Architecture: Evolution over Time

The 8th century Islamic conquest of Persia brought about what is called the Khorasani style of Persian architecture. This style originated in Khorasan, a historical region comprising northeastern Iran and parts of Afghanistan and Central Asia, and was a byproduct of the massive cultural and literary shifts which succeeded the rise of Arab Islamic rule in the region.

Though Khorasani style emerged after the Arab conquest of Persia, it borrows heavily from pre-Islamic designs.

A powerful example of this style is shown below in the Masjed-e Jāmé (‘Friday mosque’) in Isfahan. The Masjed-e Jāmé showcases the change in Iranian Islamic architecture over twelve centuries, spanning from Abbasid era (~750–1258) to the Safavid era (1501–1736).

Masjed-e Jāmé mosque

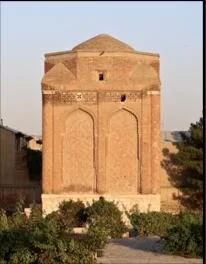

Between the 11th century and the Mongol conquests of the 13th century, the delicate Razi style of architecture emerged. Sometimes called the renaissance of Iranian art, the Razi style drew upon quick march of scientific and artistic advancements in Islamic Iran. The style was born in the city of Rei located in the Ray or Razi region, and is characterized by towers, open corridors, vegetative labeling, and use of alabaster stone. Also notable in this style was the shift from single-function buildings to those with many purposes: communes were built which could contain a school, park, hospital, meeting space, and more.

Around 1259 AD, following the Mongol conquest of Iran, building styles assumed the Azeri style, also known as the Azerbaijani style. Much less detailed and delicate than Razi style, Azeri buildings were simpler and vastly produced. One can see the distinct difference in the styles below between the Razi style Red Dome of Maragheh (simple, towering, traditional) and the Azeri style of the Nakhchivan School of Azerbaijani (simple, contemporary).

Nakhchivan School of Azerbaijani

Red Dome of Maragheh

Contemporary Iranian Architecture

The rise of the Pahlavi dynasty in the 1920s is often cited as the beginning of the modern period of Iranian architecture. The Pahlavi style was heavily influenced by Western European architecture and reflected the hope for a new and better society present during the period. Tehran in 1920-30s became a locus of innovation; the urban renewal program under Reza Shah was the first systematic attempt at urban planning in Iran.

The architecture in the contemporary period is indicative of the accelerated modernization that occurred in Iran under Reza Shah (1925-41), resulting in a more international take on Iranian architecture. A blend of styles occurred at this time as well, where projects such as the National Museum of Iran aimed to mirror aspects of historical national heritage, while others such as Tehran University aimed to merge traditional styles with modern ones. Other architects decided to pursue completely new designs, such as Heydar Ghiai who created works such as the Parsian Esteghlal Hotel, formerly known as the Royal Tehran Hilton.

Parsian Esteghlal Hotel

Parsian Esteghlal Hotel

Certainly one of the most distinctive modern pieces of architecture in Iran today is the Azadi tower (formerly Shahyad building), which stands as a landmark in the center of Tehran. The building is known for its grandeur and well-constructed incorporation of traditional Iranian architecture styles such as squinches and ruins of Ctesiphon, and also its roots in its association with the deposed Shah. It became the landmark for protests against the Shah’s regime soon after construction in the mid-1970s, and it was expected to be destroyed as it was technically the Shah’s project. Yet, it was transformed in name (Azadi means freedom) and in its rebranding, now stands as a symbol of freedom for Iran.

Azadi Tower

Contemporary Iranian Architecture: Economic Considerations and Government Oversight

Modern Iranian architecture has enjoyed periods of economic prosperity and hardships, reflected in the caliber of architecture built, as well as the purposes of the architecture. The political landscape has also had a strong effect on Iran’s architecture. There are three modern periods between the end of the Second World War and the overthrow of the Pahlavi regime in 1979 that reflect these considerations.

Between 1941 and 1963, Iran experienced a period of national resurgence following the allied Anglo-Soviet occupation of Iran from August 25 to September 17, 1941. Although Reza Shah Pahlavi had declared neutrality in WWII, Iran remained part of a strategically critical area known as the “Persian Corridor”. As a result, the country actually experienced political gains in this period, despite the allied invasion.

Iran was able to secure a treaty of alliance with the Allied Powers. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin agreed to recognize Iran’s territorial integrity and independence. Furthermore, by declaring war on Germany, Iran also secured membership in the burgeoning United Nations.

Iran in the waning days of WWII however, was not without its problems. The period was marked by resource scarcity and high inflation which economically crippled the middle and lower classes.

Despite this, the architecture following the occupation is generally categorized as one that valued nationalism, national identity, and goals for the future. In 1947, the National Development Plans were unveiled, which eventually became a seven-year plan that critically influenced architecture until 1963. The plan pushed for economic revival, raising the standard of living for Iranian citizens, and creation of commissions to oversee progress.

Despite the goals that the plan recommended, Iran’s priority in this period was postwar reconstruction. Iran, still recovering from a slow economy, could only produce architectural symbols of the great national revival it pursued. Monuments were built on a small scale, and although well-crafted, many pieces built in this period did not attain high levels of architectural excellence due to the economic constraints of the time. Mainly during this time, architectural progress is best noted on the domestic, not the public, front. Leading up to WWII, the traditional style of Iranian homes followed a Paradise Garden template, which included a courtyard and one to two stories, mainly built of brick or adobe by masons. Interiors to these houses were ascetic, containing little furniture, and utilizing the environment to the buildings’ advantage, akin to the techniques used by the ancient “windcatcher” architects.

After WWII, and after Iran’s encounter with the West, the interior of many of these houses were changed. Houses now incorporated furniture, a result of the need for single function rooms such as dining rooms. When this new style was being incorporated, many houses divided the furniture sides, for guests, from the traditional carpeted sections, for family. Public infrastructure and civil planning reflected further the integration of Western architecture with traditional Iranian styles; in some areas, roads and bridges were constructed to make way for the increasing introduction of cars in Iran. Although economic constraints prevented major public cultural monuments or widespread civil planning from being created, the country had entered a new era of modern, technology-seeking architectural goals.

Between 1963 and 1968, a third development plan was enacted in Iran. This period included more public-oriented infrastructure, both physically in the architectural endeavors, and socially in the spheres of healthcare, trade, and education. The Shah’s leadership during this time brought stability to the region, especially through improving relations with the West, and opportunities of foreign investment as well as expanded relations with the international sphere. This direction for Iran was controversial domestically however and was believed by many to directly clash with traditional Islamic values; this controversy was a factor that catalyzed in the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Throughout the 1960s, however, Iran experienced developments in architectural planning and design, showcased to the world at-large through initiatives such as the Shiraz Arts Festival. Professionally trained architects, now graduating from esteemed architect schools after the war, populated Iran’s landscape and made considerable additions to Iran’s architecture as well. Public achievements such as the Tehran Sports Center, built to reflect both modern technological feats, such as a water reservoir combining an irrigation system with water sports and recreation, also relied on the traditional Iranian ziggurat for aesthetic and design purposes. Many of these returning Iranian professionals were trained in Western architectural styles, which influenced building plans significantly. Unfortunately, many of these plans failed to consider economic or environmental constraints and did not afford much thought to adaptive community systems, or availability of resources in Iran at the time. Because of this, a six month ban on construction in Tehran was enacted in 1963 to counteract the material shortages that Iranian architects confronted.

The last major architectural period is characterized by the advancement toward, and eventual realization of, the Islamic revolution of 1979. The increasingly Western-centric civil architecture that populated Iran from WWII until the revolution was completely rejected by the new regime’s first leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, who categorically identified Western aesthetics as an image of regression into secularism and loss of tradition. As a result, architecture in post-revolutionary Iran stepped back from the progressive trend of the intervening 1940s to 1980s years, and re-focused on traditional Islamic representations of art and architecture. Western infrastructural expressions were banned or reconstructed to reflect traditional Islamic technologies and styles, and more intensely, many of these non-Islamic aligned buildings were torn down completely. The decade following the 1979 revolution was a death sentence for the architectural guilds, and many architects were incentivized or forced to leave the country to make way for the isolationist and nationalist approach of the era.

However, after the 1988 war with Iraq, the contemporary status of Iranian architecture was reified once more. An “Era of Construction” emerged in which Iranian architecture once more became heavily engaged with the construction of modern houses, public projects, and the combination of traditional Iranian architectural styles with new technological advancements. Buildings are typically built under two auspices: the appropriate respect for traditional Iranian styles along with acknowledgment of the available resources of the region, along with the incorporation of modern building materials and machines such as ready mixed concrete trucks or factory-produced construction products.

Contemporary Iranian Architecture: Economic Considerations and Government Oversight Case Study

Although Iranian architects are experiencing a greater degree of freedom today than in the 1980s, there have still been events that place considerable pressure on construction projects in Iran. In 2007, during President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s tenure, Iranian architects experienced issues with building availability once more. The UN Security Council unanimously decided to impose severe economic sanctions on Iran due to their nuclear program, and America specifically placed considerable pressure on Tehran to comply with UN nuclear conditions via increased military presence, seizure of Iranian agents, and more. This was not the first time that constraints had been placed on Iran by the international sector, but they were significantly influential in their restriction of Iran. As architecture is affected in times of political and economic shifts, so it was in 2007 as well. President Ahmadinejad initiated an expedited housing reform plan, which reflected the compounded effects of an inflated rent system and external fiscal issues Iran was subjected to at the time. In this plan, a rhythmic and speedy construction process was used to build several new housing compounds in Iran. These housing facilities were built under the Kayson group, and the houses were created to specifically mirror the socio-economic signals that Ahmadinejad wished to project to the international sector at the time. Ahmadinejad suggested that subsidy reform could be the solution to the economic downturn that Iran was experiencing and argued that his economic approach would allow wealth to be more fairly distributed among the upper and lower classes. Posited as a gift of the state, the houses were available to the rising middle class under the condition that the inhabitants would become indebted to the state and would be willing to expose their support of the government publicly. Samaneh Moafi’s article on this topic summarizes the intersectionality between the Kayson houses and Iranian citizens as such: “A family meal in the open kitchen of a Kayson house in Iran and the habits around its preparations and service are contingent not just on locally articulated religious and cultural practices but also on an architect’s conception of gender roles and class identities, a president’s populist policies, an anti-imperialist tie of brotherhood between two statesmen, the sanctions of a United Nation’s Security Council, and the murky business of a private developer.”

Contemporary Iranian Architects

Despite periods of economic and political uncertainty, since the Islamic Revolution, support for modernization of architecture and especially for technological advancements, has been widespread. The intellectual and architectural communities of Iran have apparently shifted their opinion from the traditionalist, Islamic Utopia approach towards modern technological expressions in architecture. Rahmatollah Amirjani, in his articles on the topic, has argued that this shift is in part a product of the increased globalization of the world, which brings with it the increased transfers of technology between nations.

The talented architects in Iran today continue to create new and innovative works of art. Many of these new projects still use existing materials and the environment to inform how their work is created, such as using perforated brick screens to give shade to residential buildings, or built-in steps in the sides of buildings that allow roof access. Architects in Iran today aim to represent the society they live in.

Alireza Taghaboni, founder of Next Office and winner of the Royal Academy of Arts inaugural Dorfman Award, is one architect to watch, and stands as an example of an artist who is able to create despite periods of economic difficulty and political instability. Among other impressive architectural feats, he designed the shape-shifting Sharifi-ha House, which includes moving blocks and windows. Taghaboni said of his famous Sharifiha House that it was in part inspired by the fact that Iranians live dual-lives. At times, they can be open and free (notice the windows facing the world) and at others they must close themselves off from the government’s watchful eye (the living room turns so the windows no longer face outside). Today, architectural pieces like the Sharifiha House and others reflect the contemporary trajectory of Iranian architecture, which incorporate traditional and modern styles.

Sharifi-ha House

Architect Mohammad Hassan Forouzanfar provides a fantastic example of how modern Iranian architects aim to combine traditional architectural styles with modern styles. Recently, he created a conceptual project called Expanding Ancient Architecture, which combines pictures of famous existing buildings and pre-Islamic UNESCO world heritage sites in Iran. See here his combination of the Royal Ontario Museum superimposed over Rostam Castle, or the Louvre protecting Chaqazanbil.

Leila Araghian, architect for the Diba Tensile Architecture studio, won a deign competition which aided her five-year design and construction process for the 270-metre Tabiat Bridge. The bridge stands as Iran’s largest pedestrian bridge, incorporating ramps and stairs which follow a meandering S-shape through the Abo Atash Park. A beautiful piece of art, it is a reflection of the excellence of architects like Araghian, who can combine purpose with aesthetic appeal.

Tabiat Bridge

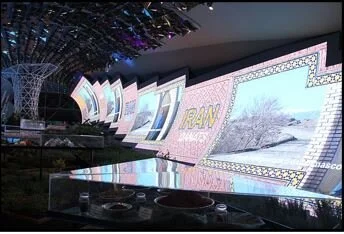

Through various architecture groups, Iran hosts a number of architecture competitions each year that challenge their talented architects to stretch their artistic imaginations. The 2015 Milan Expo, hosted by New Wave Architecture is one such example of how competition motivates these architects. Architects Lida Almassian and Shahin Heidari entered the competition with their “The Persian Garden”, which attempted to combine exploration, culture, and organic matter into a self-propagating system. This was accomplished through transitory aspects of the structure that integrated its environment with its design. For example, the structure, shaped like a tree, offers shade in its shadow while also becoming a rain shelter if need. Its ventilation allows for the natural directing of the water flows, and the pavilion contains solar panels to provide energy.

The Persian Garden

An informative video with additional information about Iranian architecture (in Persian)