Publications

AIC White Paper

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

2009

The ongoing promotion of coercive diplomacy, based on a "carrots and sticks" framework, and the continuing threats of military action against Iran - "all options remain on the table" - have failed to achieve their stated objectives, which is to change Iran's behavior in areas such as uranium enrichment, support for "terrorism," opposition to Middle East peace and human rights violation. These policy approaches are based on false assumptions about Iran, an incomplete understanding of the Islamic Republic, and a problematic definition of issues standing between the two governments. They also fail to realize that, as long as Washington remains hostile to Tehran, the best option of the Islamic Republic in relations to the U.S. is to maintain the prevailing "neither-peace nor-war" status quo.

By Elliott Morton, AIC Research Associate

As the 2024 U.S. presidential election looms just a few short months away, many Americans’ minds are focused on the race between former president Donald Trump and Democratic nominee Kamala Harris. The contest carries tremendous implications for foreign policy. While the candidates’ approaches to conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza may be two of the most discussed foreign policy matters at stake, future US-Iran relations also heavily depend on the outcome of this election. Below, I will map out the possibilities for each candidate’s Iran policy should either be elected. While we cannot predict the future, the unusual circumstances of an incumbent vice president and former president competing for the White House allows for greater insight into future policies based in part on previous actions. This article will compare the Iran policies of the Trump and Biden-Harris administrations and will evaluate their likely impacts on Iran policy in a potential future term.

By Dr. Hooshang Amirahmadi, AIC President

Abstract

The Middle East is engulfed in a sustained conflict spanning over 70 years with no end in sight. The core contributing factor is the imbalance of power between nuclear-armed Israel and its regional adversaries. Achieving peace will require a balance of power, akin to the nuclear equilibrium established between Pakistan and India. Currently, I trust, Iran is the only country determined to build nuclear weapons and it will ultimately build the bomb. This essay outlines the arguments for and against a nuclear Iran. Considering global and regional experiences, proponents appear to hold a more valid, albeit unpopular, argument. In pursuing nuclear capabilities, Iran must overcome significant challenges and meet stringent prerequisites, which are detailed in this essay. As Iran cannot be stopped to build nuclear weapons, Washington is better advised to coopt rather than confront Tehran. This is a risk well worth taking. I conclude that, for peace and economic growth, the Islamic Republic must relinquish its hostility towards the United States and Israel, as well as its support for radical proxies. Such changes, in exchange for nuclear capabilities, would foster Iran's self-reliance and prompt the regime to adopt a more peaceful stance towards its citizens, the region, Israel, the US, and the international community

By AIC Reserach Associate Tristan Gutbezahl

Western perceptions of Iran possessing an exclusively Middle Eastern foreign policy obscure the country’s growing interests in Central Asia. The region’s potential as an outlet for political and economic maneuverability in the face of sustained Western sanctions has placed Central Asia at the forefront of Tehran's geopolitical ambitions: President Raisi designated improving relations with Central Asia as “one of the first priorities of the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran" in 2022. Despite Raisi’s ambition, Iran’s moribund economy and international isolation limits its ability to woo partners in Central Asia. This article will explore Iran’s historical connections, current policies, and future vision for a region its ancestors once considered indispensable.

Op-Ed by AIC Communications Associate Samuel Howell

A cup of coffee can change the world. This statement might seem idealistic, but a look beneath the surface reveals some important and overlooked aspects of the coffee industry. Because of its affordability relative to other drinks, versatile brewing methods, and strong cultural ties, coffee is popular almost everywhere. It is currently consumed daily by 1 billion people in a variety of places around the world, from rural villages to bustling megacities. The modern growth of cafes alongside the globalization of coffee has also fostered a unifying and international love of cafe culture that is continuing to spread even today. This culture has more recently regrown roots in Iran, despite the country’s prolonged diplomatic isolation and economic downturn. Here, cafes play an interesting role in creating positive change, while confronting the negative effects of authoritarianism and an uncertain domestic situation. Below, we will explore the social, economic, and political aspects of cafes that are helping to foster development and democracy in one of the earth’s oldest nations.

By AIC Research Associate Brooke Lowe

Following Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s ascent to office on August 3 2021, Iran has witnessed several shifts in its foreign policy pursuits and overall agenda compared to those under former President Hassan Rouhani. While Raisi has been cautious on the foreign front, several significant changes have taken place, including an increased focus on relations with Russia and China. In Iran, although the President guides the direction of foreign policy, he is just one member of the Supreme National Security Council, which is the body responsible for establishing Iran’s national security policy. Therefore, while Raisi has the potential to alter the direction of foreign policy, he requires support from other actors. Nonetheless, Raisi finds himself leading an Iran with growing regional prominence and likely sees little reason to take major risks or even to negotiate with the West.

By AIC Research Associate Brendan Rettberg

A key component of the Iranian Revolution was that Ayatollah Khomeini’s Shia Islamist ideology should be exported across the Muslim world. This goal was explicitly articulated by Khomeini and his fellow revolutionary leaders in multiple political writings and speeches during the period. A speech penned by Khomeini on the eve of the Iranian New Year in 1980 reveals his dedication to spreading the ideas of the revolution. In it he declared, “We should try hard to export our revolution to the world, and should set aside the thought that we do not export our revolution, because Islam does not regard various Islamic countries differently and is the supporter of all the oppressed people of the world.” Furthermore, the constitution of the Islamic Republic states that its “mission is to realize the ideological objectives of the movement and to create conditions conducive to the development of man in accordance with the noble and universal values of Islam.” The constitution also declares itself to be “the necessary basis for ensuring the continuation of the Revolution at home and abroad.”

By AIC Senior Research Fellow Andrew Lumsden

Since the inauguration of President Ebrahim Raisi in August, how Tehran’s new conservative government will approach diplomacy with Western powers concerning the future of the 2015 nuclear deal has largely dominated discussions of Iranian foreign policy. On that front, talks, since Raisi took office, which have only recently restarted, remain marred by lingering uncertainties. The Raisi Administration, however, has been extremely active in diplomatic engagement with Iran’s regional neighbors, surprisingly even including its longtime adversary, Saudi Arabia.

Beginning in April of 2021, Tehan and Riyadh have so far engaged in four rounds of bilateral talks, with negotiations having been initiated under former President Hassan Rouhani, and continued under Raisi. Both sides have expressed positive attitudes towards the talks, with Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Minister calling them “cordial,” and saying that Riyadh is “serious” about engaging with Iran and bringing stability to the Middle East. Iran’s Foreign Minister, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, expressed similar sentiments in October, saying that talks are “moving in the right direction” and that the two sides have already come to some agreements.

By Govind Ramagopal, Research Fellow

I. The foundations of effective diplomacy

With the election of Barack Obama in 2008, there was hope in the US and around the globe that after years of war, not only would America pursue a more restrained posture towards the world, but towards the Middle East especially. Interest in President Obama’s election was high in Iran, and many warmly welcomed his victory as they felt it would mark a break from the Bush era. Throughout the campaign, the new President had stated on multiple occasions that he would pursue diplomacy with America’s adversaries, without preconditions, and this policy change included Tehran in its formulation. The appreciation of Obama’s victory even extended to the upper echelons of the Iranian government. The Speaker of the Majles, Ali Larijani said: “the Iranian government is leaning more in favor of Obama because he is more flexible and rational, even though we know America’s policy towards Iran won’t change much.” There was nevertheless an air of caution that pervaded both sides’ thinking, as the new American administration was on the other end of the ideological spectrum from the Ahmadinejad government that was steeped in a conservative worldview. Yet, President Obama continued his outreach to the Iranian people, and through those entreaties, to the regime itself. He was the first US president to mark the occasion of Nowruz, or Persian New Year, where he felicitated Iran’s rich history and remarked that “Iran could take its rightful place in the community of nations”.

By Research Associate Lauren Elmore

Climate change is already affecting Iran on a multitude of levels and will only continue to grow more serious over the years. This is a wide-ranging and expansive problem, which is unlikely to be resolved without global action.

Iran’s environmental issues are increasingly causing economic difficulty, severe health consequences, and widespread societal strife. Though the Iranian government has recognized climate change to be a problem, mitigation efforts have been minimal, in part due to the country’s poor economic situation.

Internationally, climate change is broadly recognized; however, combatting it is a half-hearted gesture. Few countries have made significant contributions to the reduction of their greenhouse gas emissions, including Iran. However, some issues like water scarcity are becoming increasingly pressing and may ultimately refocus regional alliances and cooperation in the Middle East.

By Research Associate Lauren Elmore

Iran, like most countries around the world, has experienced severe economic and social impacts due to SARS-COV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Unlike other countries, however, Iran has been hit particularly hard as a result of (1) an especially strong early wave with limited government response, (2) general public distrust of government directives, and (3) existing economic difficulties, which further complicated the government’s ability to respond with effective health measures. These factors, in turn, have resulted in an increased level of social unrest across the country.

International aid for Iran during the pandemic has been mixed. Russia has been a strong partner for Iran and has continually provided it with medical equipment, vaccines, and research regarding the virus. China has also remained a key ally to Iran, predominantly providing economic support. However, Western relations have remained poor as a result of a deep-seated distrust among the countries. Aid during the pandemic was consistently blocked by both Iran and Western nations.

Given the continued spread of the virus in Iran, the ongoing difficulties between Iran and the West, and the broad lack of vaccines in the country at the time of this writing (June 2021), it is very likely that these difficult economic, health, and societal consequences of the pandemic will last well into 2022 and beyond.

Guest Article, by Franklin T. Burroughs, Ed.D.

The Great Game of the nineteenth century between the British and Russian Empires over Afghanistan and neighboring territories also threatened Persia, now known as Iran. This confrontational ambiance

and the negative implications created both fear and distrust within the Government of Iran toward England and Russia and prompted the acceptance of the United States as a more trustworthy foreign power.

The United States entered the Iran relationship with what Robin Hobb would term “the velvet glove that cloaks the fist of power.” America used a level of diplomacy that convinced the Iranians that the U.S. had their interest at heart and greatly heightened Iran’s expectations related to the American government. The trust reached such a level that the shahs in power appointed two Americans, Arthur Millspaugh and Morgan Shuster, treasurers-general of the country. The U.S. display of relatively soft power persisted until

the mid-twentieth century.

By Senior Research Fellow Gabriela Billini

Going beyond the JCPOA in pursuit of a stable Middle East

While the United States and Iran each calculate the best way to return to the JCPOA, pressure on the Biden administration continues to mount from domestic parties and concerned US allies abroad. Many argue that the JCPOA as it exists today simply does not go far enough to regulate Iran’s regional posture and related activities. The extent to which Iranian authorities would realistically consider renegotiating the nuclear deal, however, is a serious concern. However, if the Iranians would be willing to return to the negotiating table to discuss regional security matters, mutually-beneficial partnerships with regional partners could be proposed in exchange.

The JCPOA can serve as a model to extend Iran’s global integration - a kind of “JCPOA Plus”. Signatories should therefore consider which states in the region are ideally positioned to engage as sponsors and allies to help establish and promote a more tenable agreement. While the JCPOA does not currently include other regional actors, the best and most sustainable solution for long-term stability of this deal is a renegotiated JCPOA that also addresses the broader concerns of regional actors, in exchange for economic and political reassurances to Iran.

By Research Fellow Govind Ramagopal

There have been a few fascinating Presidential elections since the birth of the Islamic Republic in 1979, but the election on June 18th promises to be one of the most consequential elections in the recent history of Iran. This election is significant as well because given Ayatollah Khamenei’s advanced age and ill health, it could be the last presidential election he presides over as Supreme Leader. Additionally, the election will be held during the ongoing COVID pandemic, where Iranians who have been suffering from sanctions induced economic hardship, have also been dealing with economic travails brought about by the COVID pandemic. While there has been no lockdown on the scale seen in Western countries, frustration about economic, political, and health related disasters and incompetence have reached new heights. The hope and optimism that permeated through much of Iranian society after President Rouhani’s election in 2013, and especially in the aftermath of the JCPOA’s passage in 2015, have long since evaporated. Now, anger and apathy are widespread amongst those with moderate or reformist political inclinations.

By Senior Research Associate, Scott Ferguson

The modern relationship between the Islamic Republic of Iran and The Russian Federation does not lend itself to a neat and singular interpretation. The prevailing sentiment is that Russia and Iran are walking together, though not in lock step, towards an anti-U.S. and Western future. There is quite a bit of evidence that supports this theory. Diplomatic, military and economic engagement between the two have been increasing in recent years. Mounting tensions between the U.S. and Iran during the Trump administration appeared to further catalyze this cooperative push. Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif has clearly stated, “In this critical situation, the relations between Iran and Russia are at their best and Iran’s will is to develop and deepen these relations.” In January, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov echoed this sentiment while underscoring their geographic proximity stating, “These are relations between friendly and close countries that are neighbors in the Caspian Sea area.” Russian commentators have actively promulgated this narrative since the early 2000s.

Similarly, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei recently outlined his belief in the importance of close relations between Moscow and Tehran in a strategic letter to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Hardliners within Iranian politics have hailed a pro-Asian, and in particular, a pro-Russian foreign policy as “the beginning of the post-American era.”

By Senior Research Fellow, Andrew Lumsden

The election of Joe Biden to the Presidency of the United States awakened hopes and expectations around the world that Washington will re-enter into the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA or ‘Iran Nuclear Deal’), a landmark agreement which relieved some economic sanctions on Iran in exchange for limits on the country’s nuclear program. During the 2020 campaign, both the Biden Campaign and the Democratic Party vowed not only to re-enter the JCPOA, but to “strengthen and extend it,” as well as use it as a springboard to a more “comprehensive diplomatic effort” with Iran.

While a Biden-era U.S.-Iran thaw is certainly possible, it must be understood that Iran’s current domestic political landscape is very different compared to when the JCPOA came to be, and may be moving in a direction increasingly unconducive to diplomacy and compromise with the West.

By Research Associate Connor Bulgrin

America’s tense relationship with Iran has provided an opportunity for several presidential administrations to earn their foreign policy bona fides. While most presidents since the Iranian Revolution have used America’s hostile relationship with Iran to prove their toughness and unwillingness to negotiate with “state sponsors of terror,” President Obama’s entry into the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) provided an opportunity for diplomacy that had not existed since the Clinton administration. In the last four years, however, the possibilities for diplomacy have been waning. Increasing bellicosity from both the United States and the Islamic Republic has provided an inhospitable environment for negotiations. In this analysis, we examine President Biden’s likely policy toward Iran and whether he will return to America’s historic policy of “toughness” or restore the diplomatic overtures of the Obama era by reentry into the JCPOA.

By Research Associate Zahra Ladha

Following the 1979 revolution and Iran’s appearance on the world stage as a regional power, the political class in Iran quickly achieved notoriety for what has been deemed to be their incendiary rhetoric and aggressive stance against the West. As a result, over the years, many an op-ed and think piece dissecting speeches and comments made by the Iranian government have been written. However, time and time again in the analysis of Iranian political discourse, a lack of understanding of Persian culture alongside outright mistranslations of these speeches have been exploited to exacerbate existing political tensions between Washington and Tehran. Over the past year, much has been made of the physical engagement between Iran and the US which many claim has brought the two countries to the brink of war. In comparison, there has been little focus on the effect of the war waged against Iran in the US media. This phenomenon which has historically relied on deliberate mistranslations of the words of Iranian leaders, has a seen a significant re-emergence under the Trump Administration. The most notable of these instances is, of course, the infamously mistranslated ‘wipe Israel off the face of the earth’ quote attributed to then president Ahmadinejad which, as well as exponentially increasing regional tensions, has been repeatedly used to justify the nuclear sanctions against Iran. However, US President Donald Trump’s three years in office has seen the continued use several older mistranslations such as the ‘Death to America’ chant, with several new additions such as the recent mistranslated ‘the White House is mentally retarded’ comment ascribed to President Rouhani, in order to strengthen the pro-war faction on Capitol Hill.

By Research Fellow Gabriela Billini

While all sovereign nations have relationships with other states for a variety of reasons ranging from economic to cultural to security concerns, some of the most important ties are with states that lie in one’s immediate region and geographic neighborhood. Such bilateral relations are helpful for garnering influence via soft power and may influence decisions a state’s government makes concerning its domestic policies and international engagement. They are particularly important for addressing key regional issues and conflicts. Iran is no exception, and has a dossier of shifting relations.

This series on Iran and the Middle East (part I) will elaborate on Iran’s connections with Middle East states and its eastern neighbors in political relations, economic, security, and civil society matters. Knowing what lies at the core of these relations is key to understanding Iran’s role in the region and can shed light on bigger issues that contribute to the complexities of the Middle East. Understanding Iran’s relationships with its neighbors is particularly important for comprehending its ambitions for regional influence. Three key features that help define Iran’s relationships with its neighbors include each state’s relationship with the outgoing Pahlavi Dynasty, the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) and each state’s relationship with Saudi Arabia.

By AIC Research Associate Nicholas Turner

Contemporary Persian Art

A modern art movement emerged in Iran in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s following the death of Iranian painter Kamal-ol-molk (Fig. 6) in 1940. His death represented a symbolic end to a rigid adherence to formalism and realism in painting, two principles which Kamal-ol-molk had championed during his life as a painter in the Qajar court. This modern movement, though it did engage with ideas that were being employed by western modern artists, was firmly grounded in Iranian artistic and cultural history. Marcos Grigorian (Fig.7), one of the most important Iranian artists of this time, used natural materials in his work, making reference to Iran’s natural landscapes and “indigenous dwellings.” Other artists like Parviz Tanavoli, drew on Iranian art’s epigraphic history with his manipulation of cuneiform and the Persian vocabulary. Tanavoli’s most well-known works come from his “Heech” sculpture series (Fig. 8). Tanavoli’s metal sculptures take the Persian word “Heech,” which means nothing, and abstracts its form into playful and emotive shapes.

By AIC Research Fellow Shiva Darian

When most people hear the terms “Iranian women” and “soccer,” they are reminded of Iran’s recently lifted ban on women entering sports stadiums.

A few months ago however, I discovered this hilarious and ironic 2015 news story about the Iranian women’s soccer team actually being comprised of a number of male players. The photos made for great laughs, but also sparked an interesting series of discussions and thoughts. Apparently, upon being caught using male players, the team manager defended the decision by stating the players were transgender. Unfortunately, this attempt to deflect the blatant cheating scandal by sparking dialogue on transgender rights was largely ignored, mostly due to the fact that the team had only won a single game that season.

By: AIC Research Fellow Gabriela Billini

INTRODUCTION

Iran and Turkey have often competed with one another for regional control, with this struggle spanning many centuries, between several empires. Today, the Middle East presents the world with a picture of many competing states seeking dominance over economic, security, and political issues in the region, especially vis-a-vis the West. With high-stakes conflicts bubbling throughout the region, and borders becoming less defined, the competition for this control has become explosive, as demonstrated by various conflicts like the civil wars in Syria and Yemen, as well as the struggles for a Kurdish state. Given the stakes, there is room for the emergence of a new regional leader (or leaders) capable of stabilizing and securing the Middle East.

Despite their historical position at odds with one another, today Iran and Turkey hold mostly complementary positions on some of the most important issues in the region,which the leaders of the two nations have certainly noticed. The result has been an evolving security relationship between the two countries, which this paper aims to explain in detail. Furthermore, given the significant number of aligned goals and interests of both countries, this paper will also explore potential areas of future cooperation and the possible benefits to both nations should they enter into a new, more substantial regional partnership.

By AIC Research Fellow Gabriela Billini

o Introduction

Religion can be perceived as a core factor in the Islamic Republic of Iran’s foreign policy. As the only state in the Middle East whose government is guided by theology further encouraged by its constant usage of religiously-imbued messages, it is easy to come to such a conclusion, despite its fallacy. It is therefore important to analyze the limitations of religion in Iranian foreign policy to understand, instead, what drives it. This paper argues that religion is nothing more than a tool leveraged to aid Iran in its aspirations towards becoming a more significant regional player. I will discuss Iran’s foreign policy and show that despite the religious discourse, Iran’s foreign policy is shaped instead by the regime’s interests. It must not be overlooked that religion is an important tool and I will show how the regime leverages it in its involvements abroad. Religion, however, is not the core principle driving foreign policies. Further, it is crucial to discuss Saudi Arabia to address how both players use religion in their competition for regional power status. Analyzing Saudi Arabia is important because it has implications for the region’s future, as well as a mechanism of comparing Iran’s activity.

By: Shiva Darian, Gabriela Billini, and Nicolás Pedreira

AIC Research Fellows

Introduction:

Allies for most of the 20th century, the United States and Iran were radically divided after the 1979 Iranian Revolution that overthrew Mohammad Reza Shah and replaced him with a theocratic government. Throughout the last 38 years, U.S. policy toward Iran has fluctuated between open animosity and cautious mistrust. Former President Obama’s unprecedented approach to U.S.-Iran relations involved increasing pressure on the nation through the implementation of sanctions, while conveying a willingness to negotiate in order to come to a deal on what was perceived as one of the biggest threats to international security.

The Framework for Cooperation Agreement was established after months of negotiations and multiple meetings with the IAEA and the P5+1 (the United States, France, the United Kingdom, China, Russia, and Germany). Finally, in July of 2015, a consensus was reached and unanimously ratified by the UN Security Council as Resolution 2231 (2015). Through diplomacy, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), or Iran Deal, aimed to establish a somewhat comprehensive resolution to an outstanding issue between the two nations.

By AIC Publication Committee Member Hamid Zangeneh

نظام جمهوری اسلامی در گذشته به خواستهای مردم توجه چندانی نکرده و با توسل به انتساب خواسته ها به تحریکات حقیقی و مجازی خارجیها به سرکوب ادامه داده است. هر از چند گاهی سر و صدای اصلاحات و تغییرات را راه میاندازند ولی میدانند که نمیتوانند مسائل را به نحوی قابل قبول حل کنند چون بقول معروف کارد دسته خود را نمیبرد. در نتیجه، اعتراضات بیشتر و بیشتر همه گیر و آشیل نظام ضعیف تر و ضعیف تر شده است.

به نظر میرسد که این بار اعتراضات به فرای عده ای تحصیل کرده که دسترسی به رسانه های مجازی دارند رفته و خطرناکتر شده است. نمیدانم که آیا نظام فکر میکند که میتوانند مجددا با دستگیری عده ای “آرامش” بر قرار کنند یا حداقل برای حفظ نظام حاضرند که تغییرات اساسی در نظام بوجود بیاورند. بنظر ما تغییرات اساسی که لازم است مسئله قیمت پوست و پیازنمیتواند باشد.

نظام جمهوری اسلام بر مبنای انحصارسیاسی و اقتصادی است. پستهای سیاسی به دوستان و آشنایان اختصاص دارد و بخشهای اقتصادی به وابستگان و قدرتمندان سپرده میشوند. درآمد نفت ازطرق مختلف درخارج از ایران در حسابهای شخصی سرمایه گذاری میشوند و به مردم کوچه و بازار سهمی نمیرسد. بانگها سپرده های مردم را چمع آوری میکنند و به وابستگان و قدرتمندان وامهای کلان در مقابل وثیقه های پوچ میدهند. بانکها اکثرا ورشکسته هستند ولی به رفتار خود در زیر سایه نظام ادامه میدهند. بقول آقای لاریجانی، رئیس مجلس شورای اسلام، فساد همه گیر شده است و بآسانی قابل حل نیست.

بنابراین اگر بخواهند مسائل مملکت را بدون خون ریزی و خرابکاری حل کنند باید از خودگذشتگی و خلوص نیت همه جانبه، بخصوص ار طرف اولیاء نظام جمهوری اسلامی، نشان داده شود. ما اگر بخواهیم کلیه خواستها و منویات مردم را ریز کنیم باید طوماری بی انتها تهیه کنیم. بنابراین ما در زیر فقط به خواستهای بنیادی که میتوانند گشایشی در زندگی سیاسی، اجتماعی، و اقتصادی ایرانیان باشند بطور سرخطی اشاره میکنیم:

Hooshang Amirahmadi, PhD

Professor, Rutgers University

The JCPOA: From Despair to Hope

The North Korean crisis has pushed the future of the 2015 nuclear deal among Iran and the P5+1 (US, UK, France, Germany, Russia, China), commonly referred to as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), into the background. Yet, this temporary situation will soon reverse itself as a powerful storm is gathering around the subject. The JCPOA, which was intended to reduce tension between the US and Iran, has been criticized repeatedly by President Donald Trump as a highly deficient agreement, and this change in the White House's attitude under a new president is the primary cause of this developing storm. Indeed, US-Iran relations have unexpectedly become highly explosive in the post-JCPOA period. President Donald Trump’s speech at the UN was a clear indication of this new situation. To mitigate this emerging danger, the policy community must overcome complacency, act with urgency, offer an even-handed and realistic analysis, and propose a fair solution.

Marielle Coleman, Research Associate

Iran is one of the world’s oldest nations. Yet when people think about the country, they tend only to think of the Islamic Republic, which represents just a fraction of the country’s history. Put simply, if the complete history of Iran was represented as a calendar year, its time as the Islamic Republic would be a little more than two and a half days. The truth is that Persia, Iran’s pre-1932’s name in the West, has a vast and rich culture, one that extends far beyond the image of Iran familiar to the Westerners today. Its history was shaped not just by forces within, but also from its interactions with other countries, including France, the focus of this paper.

Relations between Persia and France were established in the 13th century after France became an important power in the region. Since then, the two countries have maintained and fostered connections nearly as often as they have disagreed and disrupted their bonds. This paper will provide a summary and analysis of the variable nature of their relations since the Crusades.

By Michael Schwartz, Kriyana Reddy, and Dr. Reza Ghorashi

Over one year has passed since the formal implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed by the US and P5+1 members (China, France, Germany, Russia, and the UK), which lifted certain “nuclear-related secondary sanctions,” on various Iranian business sectors.[1] All parties to the JCPOA agreed to implementing it “in good faith and in a constructive atmosphere” and to “refrain from any policy specifically intended to ... affect the normalization of trade and economic relations with Iran.”[2] While initially the JCPOA was met with optimism, critics in both Tehran and Washington have challenged the effectiveness and potential benefits of the agreement. Iranian public opinion remains steadfastly in support of the deal, but the reality of Iran’s long transition from economic isolation has curbed some enthusiasm. While the JCPOA has created significant opportunities for economic growth and normalization, the Iranian public has not yet seen many tangible economic benefits.

By Kriyana Reddy, Research Associate

In July 2015, the United States partnered with other members of the P5+1 (China, France, Germany, Russia, and the United Kingdom) along with the European Union and Iran to sign the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).[1] The plan was officially implemented in January 2016, and the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the U.S. Department of Treasury issued numerous accompanying documents as guidelines on the JCPOA.

Both due to - and also despite - this abundance of language, there is often confusion surrounding what is and is not permitted in U.S.-Iran business operations under the new agreement. Hence, this article seeks to clarify some of these guidelines. Imagine this as “OFAC 101.”

By Dr. Hooshang Amirahmadi

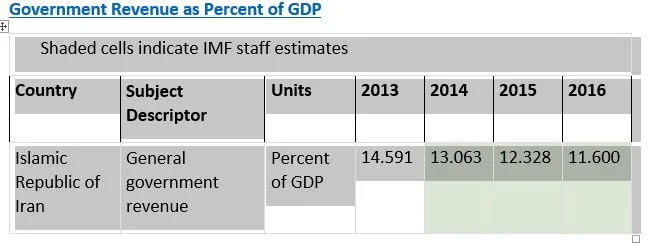

The Iranian economy continues to face serious difficulties, with seemingly no solution in sight. The one area which the Rouhani government wishes to take credit for is with regards to inflation. Indeed, under the presidency of Hassan Rouhani, the inflation rate has reduced significantly relative to the tenure of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. However, as critics have maintained, this decrease has been due primarily to the ongoing recession that plagues the country, rather than government policies. For the most part, the country remains mired in a deep economic depression, with little to show in way of recovery for the average Iranian.

By Samuel Howell, AIC Research Associate

In 2022, the death of Jina (Mahsa) Amini in Tehran created a chain reaction of social unrest that culminated in months of widespread protests in Iran. These protests championed a number of causes, including improved economic conditions, the removal of certain government leaders, and, above all, equality and justice for women. Results of these demands have been mixed: while they have inspired many women to act in solidarity and refuse to obey the laws that control their personal lives, no official government policies have changed.

With this in mind, it is a good time now to reflect, not just on the most recent protests that made news in the West, but on a much broader history of the fight for women’s rights in Iran, neighboring Iraq, and the regions of Kurdish territory within their borders. While these places have been at odds with each other for much of recent history, the story of their efforts regarding women’s rights share similar foundations and headwinds within the broader struggle for social change. This article will focus on recent women's rights developments within Iran, Iraq, and Kurdistan, what their struggles mean for the progress of the region, and the international implications of these events.